[Note: this is a sequel to my previous post: Systemically important cryptocurrency networks, which critically examined how certain digital tokens parasitically leech off the U.S. banking system. There is an accompanying Appendix to this document as well.]

The second half of 2020 saw a large set of draft regulations and proposals surrounding cryptocurrencies and specifically, “stablecoins.”1

For instance, in July, the influential Group of Thirty published its investigation into digital currencies and stablecoins. In late September, the E.U. announced an expansive regulatory framework called Markets in Crypto Asset Regulation, or MiCA.2 A month later the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the top global stability watchdog, released its “final” report on what they called global stablecoins (GSCs). A month after that, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) released a report specifically looking at stablecoins.

A few days later there was a flurry of tweets and articles written up in response to the newly proposed STABLE Act in the United States. And coincidentally, this past month the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets released a report on stablecoins that came out swinging against “multi-currency” projects like Facebook’s Diem (formerly Libra) as well as broad pieces of enabling infrastructure. 3

While each was written by different sets of authors in different jurisdictions, all had some common ground: regulation and risks of panjurisdictional commercial bank-backed “stablecoins.”4

This post will go through some of the background for what commercial bank-backed stablecoins are, the loopholes that the issuers try to reside in, how reliant the greater cryptocurrency world is dependent on U.S. and E.U. commercial banks, and how the principles for financial market structures, otherwise known as PFMIs, are being ignored.5

Let’s start in reverse order.

PFMIs

What are the PFMIs?

We have discussed the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMIs) before. It is an evolving set of principles and guidelines for financial market infrastructures (such as CSDs, CCPs, payment systems) that are maintained and updated based on research and collaboration between two international regulatory bodies: BIS and IOSCO. Their joint 2012 paper is considered the gold standard and is frequently cited in the press, academia, and regulatory bodies.

For the purposes of this article, we will look at just once slice of the 2012 document. Principle 9 of the PFMIs states:

An FMI should conduct its money settlements in central bank money where practical and available. If central bank money is not used, an FMI should minimise and strictly control the credit and liquidity risk arising from the use of commercial bank money.

We have ample evidence from the 2007-2009 Great Financial Crisis (and other eras) that dependence on commercial banks is subpar and adding yet another (underaccountable) layer on systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) is not ideal. 6

Without going into weeds, the PFMIs and the committees involved in drafting them, state and then re-state the importance of reducing credit risk exposure to commercial banks. Yet in all instances today, almost every collateral-backed stablecoin that has thus far been issued does so through tokenizing deposits custodied at commercial banks.

This is improper for a variety of reasons and there are remedies and solutions. For instance, while we await liberalized access to central bank digital accounts (CBDAs) or currencies (CBDCs), setting up “narrow banks” or FedAccounts have been highlighted as complimentary solutions in the United States.78

When presenting these alternatives in public — especially on social media — a noticeable amount of “fist shaking” and “pearl clutching” occurs from partisans unaware of how reliant stablecoins are on the U.S. and E.U. commercial banking systems. 9 10

For example, a number of prominent cryptocurrency promoters claim that draft legislation (such as the STABLE Act) would destroy innovation or even blockchains themselves. 11

As it stands today, non-compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) is strictly speaking not “innovation.” It is regulatory arbitrage which can create a race to the bottom that may harm consumers.1213 Commercial bank-backed stablecoins are ‘innovative’ insomuch as they are not playing by the same explicit rules that other bank-like entities have to.

We will discuss them at length further below but currently – as measured in trading volume – the two most “popular” commercial bank-backed stablecoins are USDT (Tether) and USDC (USD Coin).14 Both claim to be collateralized by U.S. dollars held in custody at commercial banks. Together they accounted for nearly 90% of all stablecoin trading volume this past year. 15

How big is that volume?

As an aggregate, in 2020, on-chain volume alone from these stablecoins reached more than $1 trillion. That does not count the exchange-based (off-chain) transactions that also use these collateral-backed coins. And problematic for policy makers: the on-chain volume was exchanged with limited oversight or surveillance sharing, which is part of the reason why various governments are moving quickly to pass laws to deanonymize self-hosted wallets that are exchanging this parasitic “e-banknote” or “shadow deposit.”161718

For example, Tether and USDC are not being stifled through the proposed STABLE Act, rather they would be required to jump through the same hoops as anyone else providing similar financial services.19 Based on how their product is used, these issuers are arguably a form of wildcat banks (from the 19th century) or what is called a shadow bank or shadow payments today. Lots of shadows!

What is a “shadow bank”?

The term itself is just over a decade old but these entities existed prior to 2007. In general they are “non-bank financial intermediaries that provide services similar to traditional commercial banks but outside normal banking regulations.”20 Readers can imagine that this type of activity is what organizations such as the Financial Stability Board (FSB) would like to keep track of.

One member of the FSB is the Federal Reserve. The screenshot (above) is a relevant portion of their mandate and why they could – in theory – be interested in obtaining information of off-shore entities that are attempting to (anonymously) use U.S. linked e-banknotes.21

“Shadow banking” is occurring off-shore through intermediaries (e.g., coin exchanges and lending protocols) that use Tether or USDC without needing to connect to a local bank who would require some semblance of surveillance such as AML or CFT compliance.2223

Based on their external messaging, multiple centralized exchanges (CEXes) claim to operate banklessly but this is a superficial: they each maintain an umbilical cord to the U.S. dollar via USDT or USDC. 24 Similarly, decentralized lending protocols such as Compound or Aave accept commercial bank-backed stablecoins as collateral and allow rehypothecation of these same tokens (or others). 25

Putting aside new proposed legislation for the moment: stablecoin issuers (administrators) have fought feverishly to categorize themselves under a “lighter” more lenient regulatory regime (money service business) despite more stringent laws covering deposit-taking activities that are not enforced, such as 12 USC 378 (a)(2) being on the books. 2627

More precisely, in retrospect specific activities enabled by commercial banks (such as issuance of e-money) were not properly regulated. Righting this wrong that exists to day – so the argument goes – all MSBs (not just commercial bank-backed stablecoin issuers) should no longer be able to conduct unregulated shadow payments or banking activities.2829

Related to the concept of shadow banking is shadow money, and clearly stablecoins fit the bill. When he was a Governor at the Federal Reserve, Dan Tarullo gave a speech, stating:

“Shadow banking also refers to the creation of assets that are thought to be safe, short-term, and liquid, and as such, “cash equivalents” similar to insured deposits in the commercial banking system. Of course, as many financial market actors learned to their dismay, in periods of stress these assets are not the same as insured deposits.”

The classic example of shadow money is money market funds which were deemed to be “money good” pre-2008 crisis. Reforms were implemented post-crisis, such as redemption gates and floating NAVs for certain money funds, but in March 2020 the Federal Reserve still had to backstop money funds via the money market mutual fund liquidity facility (MMLF). Last month the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets released a report highlighting the need for further reforms to money market funds.

If consumers and investors think stablecoins are the same as insured deposits because they are “backed” by insured deposits at a commercial bank, they are clearly not. Does this mean that if stablecoins become big enough, the U.S. government would bail the sector out just like they have bailed out other shadow money investors? This is an open question but the answer should arguably be no. 30

While regulators have informally discussed systemically important cryptocurrencies networks and potentially overlap with PFMIs, to date there have been few discussions in long-form prose.31 Let us check back in on this topic next year.

Double the credit risk

As mentioned above, the credit risk (solvency) of commercial banks is worse than central banks.32 During the 2007-2009 financial crisis, while a number of commercial banks received direct taxpayer-funded bailouts that immediately underwent public scrutiny, the entire financial industry was effectively propped up through the coordinated actions of central banks and finance ministries around the world.

We could always argue about which policies should or should not have been implemented during that time. The Dodd-Frank Act was just one set of legislation that was passed in an attempt to prevent another, similar systemic crisis from happening again.

What does this have to do with parasitic stablecoins?

Transactional users and speculators of commercial bank-backed stablecoins are faced with at least two potential credit risks:

- the credit risk of the stablecoin issuer

- the credit risk of the commercial bank that the stablecoin issuer uses as a custodian

A conventional bank account exposes to the account holder to a single level of credit risk, the risk that the bank becomes bankrupt and is unable to meet its liabilities to account holders. In most developed countries and many developing countries, deposits are protected by a national deposit insurance scheme ranging between tens and hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Even if Signature Bank or Silvergate Bank have impeccable credit quality, they are not the lender of last resort. They rely on the implicit and explicit backing of the FDIC and the Federal Reserve.33

As a result, stablecoins present a double layer of credit risk. There is the risk that the issuer of the coins fails and the risk that the party holding the reserves (e.g. a bank, fails). Generally stablecoins would not benefit from the deposit insurance provided for bank accounts.34 Where the issuer invests in a more complex range of assets to act as reserves, such as debt instruments, it also exposes the stablecoin holder to the risk that assets fall in value, which can be an issue, even for relatively short-dated assets, where reserves have to be liquidated. 35

This raises a major question: who bears losses, the issuer or the holder of coins? An issue banks deal with (to a certain extent) by having to set aside regulatory capital.3637

In other words: a stable coin backed by commercial bank deposits has worse credit risk than simply having money in the bank because it would not benefit from any deposit insurance scheme.38

CBDCs

Tangentially related to the PFMIs are central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). Public discussions surrounding the regulation of stablecoins often neglects prior research conducted by central banks, industry, and academia.

For instance, several years ago, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) published one of the most widely cited papers on the topic of CBDCs. In it, the so-called “money flower” Venn diagram illustrated how existing money could be categorized:

As we can see, the current crop of stablecoins (such as USDC) and cryptocurrencies (such as Bitcoin) are clearly in different categories from CBDCs.

Representatives of coin lobbying organizations, such as the Chamber of Digital Commerce, makes the common mistake of conflating the two:

Are commercial bank-backed stablecoins a central bank digital currency (CBDC)?

No. There is a lot of commentary which blends stablecoins with CBDCs but they are not the same. Unless a stablecoin is backed by reserves at the central bank or issued directly by a central bank, a stablecoin marketing itself as a CBDC is being dishonest.

Furthermore, the DC/EP initiative in China is not a CBDC. It is a liability of an intermediary that is not the People’s Bank of China.39

Are CBDCs a stablecoin?

No, although in theory central bank reserves could be tokenized and put onto a blockchain. But that’s not what is happening today (yet).41

Any other reasons why stablecoins are lumped together with CBDCs?

Stability. Credible central banks such as the Federal Reserve, provide a reliable unit-of-account such that more than two dozen countries “dollarize” their domestic economies with it. This article will not go into the merits or demerits of issuing CBDCs or if a blockchain is needed in doing so.42

Ironically, while some vocal coin promoters have claimed a “hyperbitcoinization” event will occur soon. But the cryptocurrency ecosystem as a whole has seen the opposite take place: rapid dollarization due to the growth of commercial bank-backed stablecoins. This is the central conceit for much of the coin world today: promoters and meme artisans often claim they are about to launch off from planet Earth all while drilling ever deeper foundations into the Earth’s crust.

For example, in the second half of 2020 at least four U.S.-based cryptocurrency companies applied for deposit-taking licenses or banking charters.43 And because of how embedded these tokens have become to “DeFi” apps, portions of it have turned into centralized DeFi (CeDeFi), which is an oxymoron.44

As a result, it has made anarchic chains less resilient which will be discussed later.45

Reliance on external U-o-A

One characteristic or function of actual “money” is something called the unit-of-account (U-o-A). A unit-of-account is used to price goods and services in an economy. On a macro level, economic aggregates such as GDP are measured by a stable U-o-A, such as the USD or EUR.

Similarly, international commerce and trade is often denominated in a stable U-o-A. In this case, foreign exchange ultimately takes place somewhere along on “the edges” but the price discovery and (often) payment settlement occurs in the stable U-o-A. 46

For instance, despite doomsday predictions, the USD is becoming more dominant – not less dominant – in financial markets.

What does this have to do with cryptocurrencies and specifically stablecoins?

More precisely, the question should be: why are stablecoins so popular?

The answer is one that has been discussed many times on this site: volatility.47 Contrary to what some promoters claim, Bitcoin is not becoming less volatile over time. As JP Koning illustrated in the chart (above), bitcoin is more volatile today than it was in early 2017 when it had a ‘market cap’ of just $15 billion or in 2013, when it was worth just $1 billion.

While some early coin investors and hoarders may be okay with rampant swings in volatility, actual users (such as day traders or remitters) desire stability. As a result, more than 20 different U.S. dollar-linked stablecoins have been created to fill that need. And unsurprisingly, because the identity of on-chain activity can be obfuscated, another set of stablecoin users are criminals involved in money laundering and terrorism, as identified by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

For the purposes of this article “stablecoin” is a catch-all term used to describe a spectrum of coins that attempt to peg a token to exogenous (external) value.48 Typically the exogenous value is denominated in USD. In terms of trading volume, the two biggest buckets of stablecoins are:

- Collateral-backed tokens such as USDT (Tether), USDC, PAX, TrueUSD, and DAI49

- Algorithmic or synthetics such as AMPL, ESD… and the older generation of BitUSD, and Nubits

In practice, nearly all collateral-backed tokens in use today are commercial bank-backed tokens that are centrally issued by a singular entity.50 In contrast, virtually all of the algorithmic tokens are launched by anonymous teams and often use a form of rebasing or Seigniorage Shares model to arrive at a value.51

The focus of this article is on the former not the latter. Let’s dive into a few of them.

Barnacles

USD Coin (USDC) is a stablecoin issued through the Centre Foundation and backed by Circle, Coinbase, and others. This entity is registered as a MSB in the United States. USDC is an ERC20 token that can be moved around the Ethereum network however the “backend” on-and-off ramps are fully powered by U.S.-based commercial banks such as Silvergate in San Diego.52

At the time of this writing about $4.3 billion of USDC has been issued. In Q4 2020, the trading volume of USDC was usually between $335 million to $1.3 billion per day.53

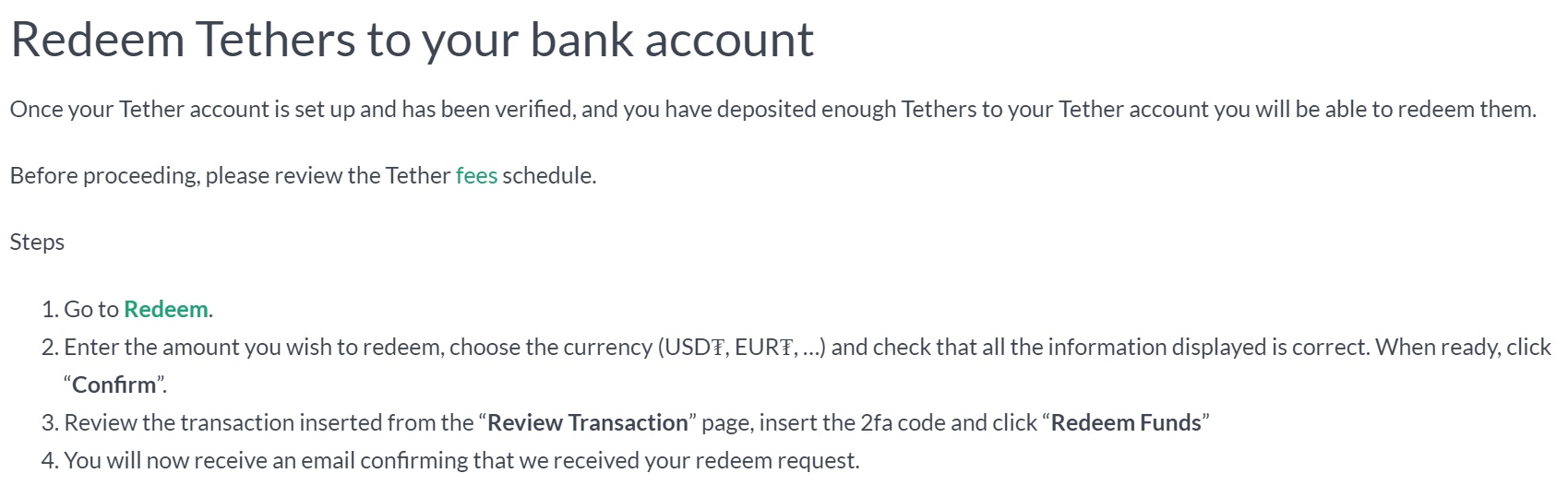

USDT is issued by Tether Ltd which is also registered as a MSB in the United States.54 Customers that want to use USDT, create an account on the Tether website and link their bank account. Then using the traditional financial system, wire cash to Tether’s partner banks. USDT has been issued onto multiple different blockchains, including Bitcoin and Ethereum. As of this writing, it is the most actively used ERC20 token.

Tether Ltd and its parent company (iFinex) have been debanked multiple times. Why?

Because both are under multiple investigations from several regulators and law enforcement (such as the New York Attorney General) for lying about their collateralization levels, among other allegations.

At the time of this writing about $21.3 billion USDT has been issued. In Q4 2020, the trading volume of USDT was usually between $25 billion to $80 billion per day.55

When it was initially launched in December 2017, DAI was collateralized only with ETH and the software company that created it, Maker, is not registered as a MSB (though it could be categorized as a “shadow MSB“). About 18 months ago, DAI transitioned to accept “multi-collateral” which includes other types of coins, such as commercial bank-backed stablecoins. In addition to being listed on most major cryptocurrency exchanges, traders can also buy DAI directly via 3rd party partners (such as Wyre and MoonPay).

However, depending on the day of the week, the proportion of U.S. commercial bank-backed stablecoins can comprise more than 50% of the collateral backing DAI (which is why it was identified by authors of the STABLE Act):

The chart (below) shows the growth (measured by ‘supply’) of the most popular collateral-backed stablecoins this past year.

Assuming the self-reported numbers are correct, this illustrates an increase in USD deposits sitting in banks on behalf of stablecoin issuers.

Note that at the time of this writing about $21.3 billion USDT has been issued and about $4.3 billion of USDC has been issued.

The bar chart (below) shows the daily trading volume of roughly the same collateral-backed stablecoins over the past three year:

Recall from above that in Q4 2020, with a few outliers the trading volume of USDT was between $25 billion to $80 billion per day and the the trading volume of USDC was between $335 million to $1.3 billion per day.

In other words, the average daily turnover for USDT was about 2 to 4 times the amount allegedly deposited with their banking partners. This likely shows that some forms of leverage, credit creation, and rehypothecation are taking place. 5657

The line chart (below) shows the total value of tokens that are locked up (TVL) in DeFi-related projects over the past ~3 years:

As we can observe above, growth of TVL substantially increased between January 1, 2020 and January 1, 2021 by about 2,000 percent. DAI contributes to about 20 percent of these deposits.

What about Diem née Libra?

With mountains of press and marketing the past 18 months, they are finally planning to launch (soon). What Libra initially proposed in the summer of 2019 (to the chagrin of regulators and payment-related partners) was that Libra would deposit user funds in multiple custody banks (like Citi) but purposefully do it in a way such that no single regulator (such as FinCEN or OCC or the Fed) would have complete oversight. That was shot down and the proposal evolved further the past year.

For example, it initially involved pegging to a basket of currencies (including SGD) kind of like an SDR, but without FSB or IMF oversight. This put commercial banks at risk in part because of non-existent AML controls. Thus the entire proposal was scrapped and a new narrative created through the use of a commercial bank-backed stablecoin similar to USDC.

There are other bits and bobs that we can dive into – such as the older generation of algorithmically “stabilized” coins Nubits or BitUSD – but that’s a separate, mostly irrelevant category of faux stablecoins.

What would happen if issuers of collateral-backed stablecoins had to obtain something akin to a bank charter?58 Last month Paxos (PAX) applied for a national charter in the United States, will other issuers do the same?

While there may be rigorous surveillance at the on-and-off ramps of USDC or USDT today, the same cannot be said for on-chain activity where the “Travel Rule” is ignored or compliance with the BSA is non-existent.

If the self-reported volumes at coin exchanges is accurate, then tens of billions (measured in USD) of these stablecoins are traded each day likely in a non-compliant manner. This undersurveilled activity is part of the motivation behind a new draft rule from the U.S. Treasury department.

For perspective, according to The Block in the first 11 months of 2020 stablecoins hit some hockey stick growth:

- Supply grew 322%

- Transaction volume grew 316%

- Daily active addresses grew 332%

And as mentioned in the first section above, total stablecoin on-chain volume surpassed $1 trillion during 2020.59

If payment processors are held liable for the activities (e.g., knowingly processing payments for scams) that take place on their networks, the argument goes, so should stablecoin issuers. In the past, both Tether and USDC have frozen funds and blacklisted addresses due to law enforcement orders, so at a minimum they should be held to the same standard as a payment processor (but are not).

Either way, it is clear that from trading activity and total-value-locked up (TVL), that the DeFi ecosystem (and all coin worlds really), are reliant on maintaining frictionless U.S. banking access.

Is this DeFi-in-name-only (DeFi-ino)? Without the on-and-off ramps into U.S. banks and most importantly – parasitic access to a stable unit-of-account, arguably the middle (TVL) activity would be a lot less than it is today.60

If the (end) goal or ethos of the DeFi world — and broader anarchic cryptocurrency universe — is to be self-sovereign and enable self-custody and not reliant on U.S. commercial banks or the Federal Reserve, the exact opposite has occurred.61

A quick DAI diversion

It is not a full barnacle however some have previously argued that DAI could become a victim of its own success. 62

How’s that? Maker’s current governance leans heavily on identifiable humans and VCs which would be hard to quickly anonymize/decentralize. Recall that its human-led governance process modified the collateralization process, allowing new types of coins and tokens to be included.63

As a result:

- Often more than half its collateral are other USD stablecoins (none of which have bank charters), so if these are shut down or liquidity severely restricted, this could impact DAI stability and/or liquidity64

- Dependence on humans to manage governance and reliance on oracles for exogenous info; these are a single-point-of-failure.

What are some solutions for Maker (DAI), whose investors and developers are identifiable?

- Act like cypherpunks, “disappear,” and go fully anonymous making enforcement more difficult65

- Eschew the current crop of oracle architecture because it is arguably a single-point-of-failure

- Remove collateral whitelists, which is something prominent developers have suggested in the past

Regarding that last point, here’s an example:

Let us check back next year to see what Maker, Compound, and Aave do with their formal governance and collateralization processes.

Breaking pegs

Worth noting that USDT, USDC, and DAI have either broken their pegs with the USD or at some point dramatically drifted from their pegs. There are multiple reasons why.

For example, in April 2017, USDT dropped below $1.00 and traded at $0.91.

Why the sudden drop?

As mentioned in a previous post, a lawsuit revealed that Bitfinex sued WellsFargo because the bank had refused to process Bitfinex’s international wires. Over a span of a few months, tens of millions of USD had been wired through WellsFargo into and out of four different banks in Taiwan which Bitfinex, Tether Ltd, and other affiliated subsidiaries had bank accounts with. At some point prior to March 2017, someone on the compliance side of WellsFargo noticed this large flow of USD and for one reason or other (e.g., fell within the guidelines of a SAR?), placed a hold on the funds. In early April 2017 Bitfinex’s parent company filed a lawsuit for WellsFargo to release these funds.

WellsFargo eventually returned the USD-denominated funds but without those funds, the peg was unable to withstand sell pressure. In other words, WellsFargo was integral to Tether Ltd’s correspondent banking relationships. About a week later Bitfinex withdrew its lawsuit but not before causing a Streisand Effect.

This was not the first time Bitfinex has been “debanked.” Phil Potter, then-CFO of Bitfinex, gave an interview and explained that whenever Bitfinex had lost accounts in the past, they would do a number of things to get re-banked. In his words:

“We’ve had banking hiccups in the past, we’ve just always been able to route around it or deal with it, open up new accounts, or what have you… shift to a new corporate entity, lots of cat and mouse tricks that everyone in Bitcoin industry has to avail themselves of.”

With this blasé attitude, it is any wonder they are under active investigations from the Department of Justice, the CFTC, and the NY AG.

The ethos of blockchainology is supposedly: “don’t trust, verify.” Above is a tweet from Paolo Ardoino, current CTO of Bitfinex and Tether.

Because no reputable firm will provide regular audits of Tether Ltd, we are left having to trust a non-credible actor.66 For instance, in April 2019, during its legal proceedings with the New York Attorney General, Stuart Hoegner, the general counsel for Tether Ltd admitted that USDT was not backed 1:1 as was claimed on their website. Instead it was running an undisclosed fractional reserve operation that was only uncovered due to this ongoing lawsuit.

In its filing with the court, Hoegner states:

“As of the date [April 30] I am signing this affidavit, Tether has cash and cash equivalents (short term securities) on hand totaling approximately $2.1 billion, representing approximately 74 percent of the current outstanding tethers.”

Executives at the parent company (iFinex) would not even acknowledge ownership of Tether Ltd until an exposé from The New York Times revealed it was the case due to leaks from the Paradise Papers (be sure to also read Amy Castor’s timeline).

We know historically that other intermediaries have lied or misled users (and investors) of what they do with deposits. For instance, during a series of investigations in 2017 in China, at least two major domestic cryptocurrency exchanges (Huobi and OKCoin) were found to have secretly re-invested customer deposits into other financial instruments.

This type of abuse is the reason why at a minimum regular audits from reputable, independent firms are required for financial service providers. Let us check in next year to see if Tether Ltd gives us more than tweets to audit.

Innovation theater

We briefly mentioned this topic at the beginning of the article but worth looking at this closer.

In the early 2010s, several prominent VC-backed fintech efforts insisted they needed carve-outs for what they knew were highly regulated activities.67 Some even hired lobbying organizations to push the “don’t suffocate innovation” meme which persists today in the form of “deregulated finance.”68

For instance, in 2014 the New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS) proposed a new virtual currency regulation dubbed the “BitLicense.” Prior to its enactment in 2015, the same sort of “everyone will leave the US” argument was made by its opponents. Throughout the second half of 2014, DFS held multiple public comment periods, the responses of which were made public. Among others, the EFF submission included the word “innovation” thirteen times. 69 Upon its enactment, a few coin-related companies claim to have left, some vowing never to return.

From a systemic risk standpoint, is society worse off because of the small handful of coin companies that had no intention of becoming compliant with a stricter MSB, let alone a banking license, left New York? No. Is the BitLicense perfect or flawless? No.

But contrary to views of partisans, entrepreneurs continue to seek it out as a stamp of approval: as of this writing there are 25 entities that have been approved for a BitLicense (although a couple overlap).70

Three years after its enactment, in May 2018, coin-focused media gave softball interviews to the “refugees” that left New York, notably Shapeshift and Kraken. Both are cryptocurrency exchanges and had (have?) legal and regulatory issues.

At the time Shapeshift allowed KYC’less transfers to take place. That changed in September 2018 after The Wall Street Journal did an investigation discovering that Shapeshift was being used to launder proceeds of crime such as the infamous WannaCry ransomware.

Perhaps publicly telling the world that you are not going to comply with the BitLicense was a redflag?71

The other prominent “departure” from New York was Kraken, another U.S.-based cryptocurrency exchange.73 The CEO publicly has written multiple articles and posts on social media for why the organization would no longer cater to New York residents. But upon closer examination, in September 2018 the New York Attorney General announced that it had evidence that Kraken was still operating in New York. While that investigation simmers in the background, a year later a lawsuit was filed by Jonathan Silverman, who had run Kraken’s OTC desk in NYC for a couple of years. He sued the exchange because they had stiffed bonus payments. It is unclear what the current status of Kraken’s business is in New York, however, a number of employees appear to reside there.74

Likewise many prominent ICO promoters made similarly grandiose statements after the SEC released its report on The DAO in 2017. That capital pooling and investments would move off-shore and the U.S. would be left behind. Regulatory arbitrage certainly did take place, with hundreds of ICOs being registered in Singapore, Taiwan, and other island nations (such as The Caymans).75 But we also saw that in practice, coin-focused developer teams continue to be hired here in United States.

Either way, as Nathan Tankus correctly pointed out:

Shadow banks have always sold themselves as providing competition to the regular banking system. And to a certain extent, they do. But its an undesirable form of competition which causes a race to the bottom.

If other nations want to put their own financial infrastructure at risk due to underaccountable shadow banking – so the argument goes – that is not a great outcome but not a terrible outcome for the U.S. banking system in terms of systemic risk.76 For example, the aim of the STABLE Act is not to globally enforce a regime: it is to prevent systemic risk in the U.S. and this can be done by strictly enforcing existing laws or enacting new laws on entities such as stablecoin issuers reliant on U.S. commercial banks.

This may sound repetitive, one cannot overstress systemic risk in the context of an underaccountable IOU layer, as Tankus once more explains:

The [STABLE Act] is aiming at systemic risk. leaving unlicensed stablecoins as a fringe financial product offered in other jurisdictions unlisted or on minor exchanges that can survive not being able to interact with the U.S. legal system accomplishes the goal

Recall that in the U.S., the only entities that have access (accounts) at the Central Bank are commercial banks. And we empirically know that the credit risk of commercial banks is worse than a Central Bank because there is just one type of money: reserves at the central bank.

Everything beyond coins, notes, and money equivalents is arguably a credit risk. Thus, not only should we want Narrow Banks and FedAccounts created, but from a resiliency standpoint at the very least we should require stablecoin-issuers to stop piggybacking on other commercial banks due to their modus operandi.

Miners and block makers

We have touched on this topic more than a dozen times on just this site alone. Let us look at this issue from a different angle.

Visa and other payment providers are liable for certain activities that take place on their networks, hence why they on-board certain merchants and off-board others that are deemed “higher risk” or whom have violated some law.77 Similarly all FMIs have various binding agreements (MSA, TOS, EULA, SLA), and the penalty for violating them could result in a participant being removed (e.g., Fedwire has a terms of service that is effectively passed on to the users of commercial bank wiring services). ISPs and telecoms are also regulated and permissioned and they can (and do) kick users off for violating their TOS.

Proof-of-work chains like Bitcoin intentionally did not include a ‘terms-of-service’ and by design did not include hooks into any legal agreement or, for that matter, attempt to integrate AML screening of participants.78

But this is just RICO theater: in an “even Steven” world, miners should be held to the same standard as other processors. Assuming some or just one of the frameworks mentioned at the top of this article is ratified, issuers can be held accountable for additional disputes that arise.79 What then of the block makers who process transactions that fail to comply with a specific jurisprudence?

For example, in terms of proof-of-work chains – in practice – nearly all of the mining pools for both Bitcoin and Ethereum are operated by identifiable entities. FinCEN’s 2013 guidance gave miners a carve-out based on the assumption that mining pools were neutral, but in practice they are not and do manually add (or censor) transactions.

For instance, at a public event in 2019, Roger Ver and Tone Vays (aka Anthony Vaysbrod) made a bet on stage regarding sending transactions – and importantly the associated fees – across both the Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash blockchains. To aide Vays’ attempt to send a below-market transaction fee, Slush (a mining pool), manually included it despite the below-market fee. They were not neutral the opposite to how miners are often portrayed to regulators.

During the frenzy of ICO mania, the rush to get into a “capped” raise meant that some speculators would “bribe” mining pools to guarantee that their transaction could be included in a specific block. For example, in May 2017, a principal at a Canadian-listed fund successfully paid more than $6,000 to an Ethereum mining pool so that his transaction could be included during the sale of the Basic Attention Token (BAT).

We could spend a couple of posts just walking through the subreddit /r/bitcoin in what is basically the de facto customer service forum in the event that a user accidentally sends a mining fee that is too big or small.

What these human-run chains independently highlight are some of the lessons from 2015. How can validators become BSA compliant or apply for a MSB license?80

Why would they need to?

In what became the “permissioned chain” or “enterprise chain” vendor world, startups like Symbiont and Digital Asset first looked at using Bitcoin mining pools to process transactions for regulated financial institutions (e.g., banks) but ultimately walked back for a couple of reasons:8182

- lack of settlement finality

- transaction fees or payments could be going to sanctioned entities

The discussions surrounding identifiable validators (this paper uses the term “KYM” – know your miner) – and the legal and regulatory buckets they fall under – has been an ongoing topic since at least 2013. The STABLE Act potentially fixes that loophole.83

Why hasn’t law enforcement prosecuted mining pool operators in the past? Partly because of coin lobbying organizations have successfully pushed a one-sided agenda on behalf of their donors and rallied external support by fear mongering about criminalizing node operators.8485

This is a red herring and is not the aim of the STABLE Act; in fact its co-authors believe that would be a bad strategy. But a bigger issue has been a lack of resources. Agencies like FinCEN have in general been underresourced and went after the lower hanging fruit (e.g., ransomware profiteers in Iran).8687 It is an open question whether they will have more resources under a new administration to look at miners.88

With the roll out of real-time transaction monitoring from many different vendors, intermediaries such as cryptocurrency exchanges and mining pools can identify and flag suspicious or illicit activity before participants can fully realize their gains.

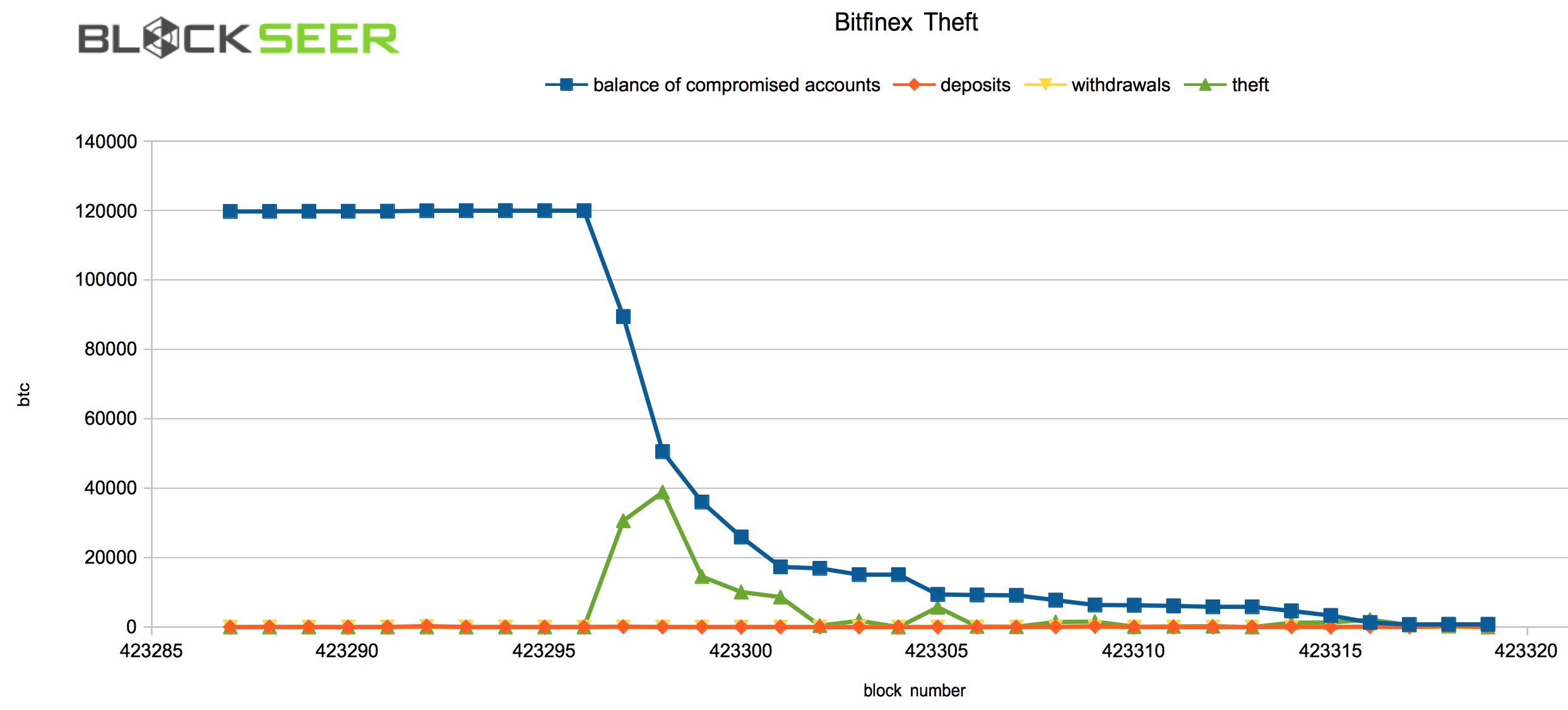

For instance, almost four-and-a-half years ago, Bitfinex was hacked and lost 119,756 bitcoins. At the time this was worth about $65 million of actual money. Today that is around $4 billion. The hacker(s) have never been (publicly) caught. Proportionally, this would be equivalent to a large commercial bank losing $20 – $30 billion USD. There have been Congressional hearings for much less.

As I have pointed in previous posts and presentations (slides 10-12), at the time 9 out-of-the-first 10 mining pools that processed the stolen Bitfinex tokens operate outside of the U.S. (specifically in China).89 If a U.S.-based financial intermediary was hacked and $4 billion in customer deposits was stolen, the fine print in the terms-of-service kicks into high gear to protect customers. Despite the billions in VC funding and headline-grabbing coin prices, similar consumer protections do not exist in the coin world.90

Even with the existence of real-time monitoring from multiple vendors, intermediaries including miners have gotten away with profiteering from processing illicit transactions that would have shook up FMIs or PSPs. Ransomware, a blight on critical public infrastructure, and the processing of its transactions are something that well-resourced prosecutors could disgorge.91

Conclusion

The motivation behind anarchic chains, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, was about creating an alternative, sovereign economy that was independent of any nation-state. But if your alternative economy uses USD (or any other fiat-linked cryptocurrency) as its unit-of-account, it is not really an alternative economy, but a subsystem subordinate to the monetary policy and pricing system of the nation that the system is supposed to be independent of.

If the aim or ethos of anarchic cryptocurrencies is to truly reduce moral hazard (e.g. taxpayer funded bailouts of banks) and systemic risks that unfortunately occur during a financial crisis, the DeFi ecosystem has a long way to reverse the current trend.92 It is not too late and in fact, client pluralism (in Ethereum) is one way to reduce systemic risk.93

“Pegged coins” are clearly fragile because they rely on an exogenous judiciary system to resolve disputes and an exogenous banking system to maintain a unit-of-account. Much of the proposed legislation above should serve as a motivation for building a more resilient on-chain U-o-A.

Perhaps the one call to action is to encourage education around “narrow banks” which could be viewed as a ‘middle ground’ between a bank charter and a MSB.94 If you are interested in learning more on the short history of commercial bank-backed stablecoins, worth re-reading the prequel from 2018 to see what has changed.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for their feedback: AC, RG, RS, RR, CW, MW, LR, JM, PE, FC, JG, JK, KV, DZ, AV, JW, and VB

- Regarding terminology, one reviewer noted: “By necessity, a stable coin is either subsidized or fictional. Dollars cost money to hold and transact in, so the only way a stable coin can be stable is if the sponsor takes risk on the underlying or uses it as a loss leader. The term has come to imply backing. Which not only is probably not true, it doesn’t necessarily need to be true. Have you ever tried to redeem a “stable coin”? Any stability of a “stable coin” is derived not from the assets backing the coin but by the ability to sell (not redeem) for a fixed amount. Which is of course true until it isn’t.” [↩]

- One commenter explained: “In the E.U., MiCA will take a while to be implemented by member states. As a result, some member states are trying to get ahead of the E.U. itself by releasing their own related laws with the aim of attracting market participants; at least until the E.U. comes to a consensus of what it will want to do. Even if being ahead of the E.U. could have short term benefits, it is also extremely important to not deviate from E.U.-wide consensus, so part of this is identifying areas that the E.U. would obviously regulate. One approach, which has been seen in Hong Kong as well, has been a phased approach to regulating cryptocurrencies by first regulating the areas that are easier to regulate (e.g. funds and fund managers, applying existing requirements to those who want to invest in cryptocurrencies), and waiting for things to develop before trying to regulate areas that are hard to regulate (e.g. custody). There is a key difference between a directive and a regulation in the E.U. A directive has to be transposed into law by the member states, which have to update their own legal systems. And when a member state is behind in transposing, like Cyprus for AMLD5, they get put in special working groups and the E.U. can even take legal action toward them. A regulation is already a law that is automatically enforceable across member states.” [↩]

- The PWG uses a broad definition: “For the purposes of this statement, “stablecoins” are the digital assets themselves. A “stablecoin arrangement” includes the stablecoin as well as infrastructure and entities involved in developing, offering, trading, administering or redeeming the stablecoin, including, but not limited to, issuers, custodians, auditors, market makers, liquidity providers, managers, wallet providers, and governance structures.” [↩]

- Most industry-driven commentary thus far seems to use the term “stablecoin” as if it is a well-defined concept. As one reviewer noted: “Assuming that there is a case for regulating a non-custodial coin, if you push the analysis to try to clearly characterize the type of coin that should be regulated, there is no other way to draw the boundary other than to say: coin that’s designed to track the unit-of-account of any currency that’s considered to be money under the law in question.” [↩]

- It could be argued that coin promoters are looking at engagement the wrong way: the onus is not on any government to bend to the needs of coin efforts. Governments should not necessarily be accommodating since it is not a reciprocal or equitable relationship. For example, Satoshi intentionally did not architect Bitcoin to be compliant with any surveillance regime, it has been an one-way conversation — mostly a monologue — from day 1. [↩]

- Recall that in both the U.S. and E.U., access to central bank accounts are restricted to commercial banks and handful of non-banks. Rather than create narrow banks themselves or seek central bank access, stablecoin issuers are arguably de-stabilizing the highly concentrated U.S. banking system by building underaccountable shadow banks on top of systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs). If an aim for “DeFi” is protecting consumers and investors, concentrating more activity onto SIFIs is not the way to go. [↩]

- One reviewer who previously worked at a central bank noted: “We need to understand narrow banks and think through what they would look like. Even I have skipped this because ‘The Federal Reserve won’t approve them so why bother.'” [↩]

- In his November 2020 speech, Andy Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, said: “On financial stability, a widely-used digital currency would change the topology of banking in a potentially profound way. It could result in the emergence of something closer to narrow banking, with safe payments-based activities to some extent segregated from banks’ riskier credit-provision activities. In other words, the traditional model of banking would be disrupted.” [↩]

- Ironically by vocally defending Tether or USDC, partisans that do not like the Federal Reserve or JP Morgan are actually defending the very entities they claim to dislike, because commercial bank-backed stablecoins are just tokenized deposits sitting in a bank. And each of those banks rely on dollar-clearing services provided by the New York Federal Reserve. In other words, the aspiration of “anarcho-capitalism” is in direct conflict with how all settlement, clearing, and payment FMIs operate today; to use a stablecoin necessarily involves needing an exogenous U-o-A maintained by the Fed. [↩]

- Quizzically, the “moral hazard” issue – that taxpayers are once more on the line to bailout commercial banks – has been glossed over by many DeFi and CeDeFi proponents. Again, the benefits of commercial bank-backed stablecoins largely accrue to issuers, traders, and speculators. These are privatized gains. Unless issuers move to a different banking model, they are ultimately relying on socialized losses by taxpayers via FDIC. [↩]

- Worth pointing out that the article above is about specific groups of people, not technology. Several years ago Steve Waldman authored the memorable “soylent blockchain” presentation. It is germane because chains – in practice – are (often) run by identifiable humans. [↩]

- One reviewer commented: “There probably needs to be a new regulatory framework, such as a narrow bank or something enabled by the STABLE Act because stablecoin issuers do not fit well in existing models. In the U.S., issuers are stuck between obtaining a bank charter versus an MSB so the current framework might accidentally muzzle innovation. If stablecoins grow to a size where meaningful risk – shadow banking, systemic risk, reduced consumer protection – are visible then how to achieve regulatory outcomes without stifling innovation? On the one hand you have the argument ‘if it looks or talks like a bank it should be regulated as one’ and on the other extreme you have ‘if it is involves a blockchain it shouldn’t be regulated.’ Both those polar extremes are wrong. Blockchain advocacy is often full of hyperbole where the centralized implementation doesn’t really follow the decentralization thesis. On the other hand, the financial industry’s default position often is: technology companies that do what we do should be as heavily regulated we are. And then financial institutions use this to curb innovation and secure their moat. The question is: how to have an enlightened discussion without interference from lobbyists in the VC-backed tech world versus the banking industry? There is probably a middle ground approach that does not result in us having to take sides. Narrow banks are one approach although it also could become political.” [↩]

- One area that cryptocurrency promoters often claim “innovation” is taking place is in the cross-border or remittance arena. Yet little more than anecdotes are provided to back up that narrative. For a detailed explanation for why this narrative is probably false, see: Does Bitcoin/Blockchain make sense for international money transfers? One reviewer commented: “This is not to dismiss the very real demand for banking services in underserved markets. The majority of companies around the world are SMEs and they provide the majority of global jobs, yet in many cases they have historically had trouble accessing banking services. This dovetails into “open banking” – access to APIs and bank data – which is a different approach from what the cryptocurrency-focused narrative often seeks to market.” Another reviewer explained: “The argument that stablecoins are not inherently as stable because they depend on the underlying creditworthiness of the backing institution is hard to argue against. At first glance, the current generation of stablecoins allow value to reach areas of new economic interest – inclusion – that traditional banks seem to ignore, yet this is likely accomplished by eschewing strict KYC gathering, AML, and CFT compliance that banks are required to conduct.” [↩]

- This article does not explore projects like USC or JPM Coin, the latter of which is ultimately backed by the balance sheet of the bank itself. [↩]

- Generally speaking, most stablecoins are issued as USD. As one commenter noted: “Recently a subsidiary of GMO, a Japanese IT giant, was authorized to issue a USD and a JPY stablecoin under New York State regulations. I think we’ll see much more of these cross-border combinations. And I don’t see regulators in New York State bowing to an emerging market central bank that doesn’t want to see its currency being wrapped into a stablecoin.” [↩]

- The (intentional) lack of on-chain surveillance is one of the reasons why a Bitcoin ETF has not been approved by the SEC. For instance, see Comments on the COIN ETF (SR-BatsBZX-2016-30). [↩]

- One reviewer noted: “Instead of saying ‘e-cash’ I would say ‘e-banknotes’ or ‘shadow deposits’. I think ‘cash’ has specific properties that most of these blockchain/account-based payments systems don’t have. It is too generous to call them cash and for the banking laws, it is the deposit-equivalent that’s the real issue.” [↩]

- Another reviewer commented: “In one scenario you effectively end up with a regulatory regime where any stablecoin issuer has to whitelist (or blacklist) the supported chains and then only custodial wallets or KYC’ed wallets can hold coin. An alternative is having to monitor activity and while this can become “theater,” compliance is still robust and the team can point to “we are doing something” that can be tweaked and tightened up. Monitoring obligations may be the route otherwise you end up having to authenticate every address as a stringent requirement. Mandatory KYC’ed addresses could make certain “digital cash” impossible to use.” [↩]

- The terms within the STABLE Act also provide latitude for U.S. regulators to create ‘narrow bank’-like structures for these types of issuers. [↩]

- For more discussion on defining “shadow banking” see Towards a theory of shadow money by Daniela Gabor and Jakob Vestergaard. [↩]

- The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve oversees two FMUs in the United States: CLS and CHIPS. CLS was launched about 20 years ago in part to reduce Herstatt Risk. In all cases, users of FMIs and FMUs have large MSAs to agree to. [↩]

- The term “Tether” itself connotes a purposeful tie to actual money. And like the term “smart contracts,” stablecoins are neither stable and nor coins. Just a risk disguised as a rational ‘crypto safe haven.’ [↩]

- One reviewer commented: “‘1-1 fiat-backed at the Central Bank’ stablecoins are close to narrow banks but far from full license banks. Lending is the risky part of the license. The Ant Group IPO debacle is in part around this distinction. We need to think through what a “just lending” bank looks like.” [↩]

- Some of these exchanges allow users to trade a variety of other financial instruments and even add leverage. [↩]

- Promoters often claim that these protocols are just tools that help the unbanked but that is another way of saying the ends justify the means. [↩]

- A detailed explanation for how and why the MSB regime has been improperly used for years can be found in: Comment Letter – Office of the Comptroller of the Currency: Warning of the Dangers Posed by the Shadow Payment System and Shadow Digital Money by Dan Awrey, Lev Menand, and James McAndrews. [↩]

- The observation around illicit deposit-taking is not new, I even wrote about it more than five years ago. [↩]

- One reviewer noted: “The best argument stablecoin issuers have is “Paypal got to do it, why cant we?” the response to which is: Paypal shouldn’t have been allowed to do it, and we certainly shouldn’t repeat this mistake now when we have a real chance to fix up all of this mess.” [↩]

- Another reviewer noted: “For stablecoin issuers this ‘fix’ could become a slippery slope resulting in a bifurcation of blacklisted versus white listed addresses (or coins). Today physical cash transactions are not KYC’ed but intermediaries have KYC obligations for a reason: because they are an intermediary engaged in regulated activities (e.g., holding client deposits). One of the innovations with cryptocurrencies was getting rid of account-based money but creating white and blacklisted addresses brings account-based money back in so if that happens why bother using it versus PayPal?” [↩]

- State intervention already occurs via taxpayer subsidies to proof-of-work miners removing a raison d’être for proof-of-work mining. [↩]

- One of the earliest discussions on this topic comes from an Australian attorney: Australian update: PFMIs on Crypto Exchanges [↩]

- We know empirically that the credit risk of commercial banks is not zero, hence why the supervisory departments at central banks regularly perform not just audits, but stress tests to see how financial institutions would weather systemic events. [↩]

- It is quite common to hear professional coin traders claim that a governmental organization like FinCEN or SEC would never shut down an entity like Tether because the knock-on effect would be devastating… that Tether was “too important to fail.” Concentration of risk this early in the game is not a good thing. [↩]

- The FDIC has a history of stepping in and protecting uninsured deposits as well. Do stablecoin issuers believe this is an implicit guarantee for future crises? [↩]

- Office of the Comptroller of the Currency’s guidance from October permits national banks to hold fiat stablecoin reserves. This supports the argument that these “projects” are inextricably linked sovereign currencies. And while it is likely that Acting Commissioner Brooks is replaced under the upcoming Biden administration, changing that guidance may not happen. While it can be rescinded it is probably not a high priority and it is clear that some banks were already holding stablecoin reserves and the guidance just gave them more cover. A major caveat comes in its footnote #5 regarding a 1:1 ratio for collateralization that we know, for example, Tether Ltd has lied about before. [↩]

- As noted in the Appendix: “Other relevant issues to maintaining the stability, or even basic credibility of a stablecoin relate to legal and operational issues. If the issuer of a stablecoin fails, the assets ideally should be in a legal structure that is “bankruptcy remote” i.e. the holders of the coins can claim the reserves in preference to other creditors of the issuer. The bankruptcy remoteness of the Libra foundation, or even the general recourse Libra holders would have to the reserves of the Libra foundation are currently unclear. For the stablecoins used in cryptocurrency trading such as Tether and the Gemini Dollar there are varying degrees of bankruptcy remoteness. JPM Coin (or almost any commercial bank-issued stablecoin) is supported by the overall balance sheet of the bank. Holders of JPM Coins would most likely be treated like any other bank account holder.” [↩]

- Another reviewer commented: “The argument for exchanges and stablecoins to have direct Fed access to my mind is about protecting retail investors. Exchanges and stablecoin issuers encourage retail investors to make fiat deposits. These deposits are uninsured and there is no guarantee that the investor will ever get the money back. Tether specifically says in its legal documentation that it doesn’t guarantee to redeem USDT in actual dollars. Retail deposits can be lent to margin traders with or without the knowledge of the depositor, and they can also be leveraged up and traded by exchanges themselves, since exchanges seem to have no shame whatsoever about commingling funds. Fees can also be high, and naïve retail investors can be vulnerable to hacking if they leave their coins in hot wallets, as I suspect many do. This whole area desperately needs the sort of consumer protection that banks are forced to provide to their depositors. To my mind exchanges and stablecoin issuers should not be allowed to take retail fiat deposits at all unless they are licensed depository institutions, which would give them access to Fed liquidity. And retail fiat deposits on crypto exchanges should have FDIC insurance.” [↩]

- A third systemic-like risk that a users faces is if and when a blockchain partitions and forks. Each issuer has a different view on handle these. For instance, according to the USDC User Agreement: “In the event of a fork of USDC, Circle shall, in its sole discretion, determine which fork of USDC it will support, if any.” [↩]

- For more information on the DC/EP, be sure to read: Understanding China’s Central Bank Digital Currency by Zhou Xiaochuan [↩]

- Note that Raphael Auer from the BIS wrote in response: “Interesting but that’s not what we know about the project.” Even if it turns out that the highly esteemed ex-PBoC source was wrong, the tweet still confirms that several things we call CBDCs are not direct claims on the Central Bank. And if they are not, maybe we should just call them e-money or similar terms for new forms of commercial bank money. [↩]

- Projects like USC from Fnality are attempting to tokenize reserves at the central bank. While formal approvals have not been made, there is a possibility that non-banks are provided a pathway to opening an account at the central bank. For example, in July 2017, the Bank of England announced that it would allow direct access to RTGS accounts to non-bank payment service providers; this was followed up with a detailed information pack in December 2019. [↩]

- What are the criteria that a CBDC must have? The BIS recently published key criteria in: Central bank digital currencies: foundational principles and core features. For a critical look at CBDCs, see “Central bank digital currency – nine key questions answered” by Martin Walker [↩]

- In fact, because there is no circular-flow-of-income, proof-of-work miners must liquidate a portion of their earnings to pay utility companies and taxes in what is effectively a stable foreign currency. See Why Bitcoin Needs Fiat (And This Won’t Change in 2018) [↩]

- There are several parallels between CeDeFi and permissioned-on-permissionless chains. For instance, introducing regulated intermediaries that collect KYC removes the raison d’etre for proof-of-work (as P-o-W was used to make Sybil attacks costly). [↩]

- From a technical perspective, if these anarchic systems were fully resilient and sufficiently decentralized, it should not matter what laws are passed or enforced. Why? Because the assumption in 2008 and 2009 was that these proof-of-work networks would be operating in an adversarial environment. Currently the end-points (on-and-off ramps) act as weak, fragile links that can be compromised. As one reviewer quipped: “Based on the outcry on social media, cypherpunks seems to have gotten soft and forgot why proof-of-work is used.” [↩]

- ‘Nominalism‘ and why it is important to legally enforceable contracts and debt is a tangential point to this. As is nemo dat. [↩]

- Even as market structure improves (i.e. new hedging products, clearing, ability to move in and out of positions cross markets), bitcoins volatility relative to actual money, persists. See: Bitcoin is not the New Gold – A Comparison of Volatility, Correlation, and Portfolio Performance by Tony Kleina, Hien Pham Thuc, and Thomas Walthe; and Bitcoin Remains Vastly More Volatile Than Traditional Currencies by Max Gulker [↩]

- Some analysts and lawyers refer to a stablecoin as a “pegged coin.” [↩]

- Note: TrueUSD (TUSD) was operating for an extended period without registering as a MSB. As of this writing, TrueCoin LLC (a subsidiary of TrustLabs) is now registered with FinCEN. [↩]

- One reviewer commented: “Any system that involves trusting some central actor (a bank, an issuer) is not embracing the core element to cryptocurrency innovation, and is mostly just a way of using money over the internet. Since stablecoins (or coins issued by tokenized deposits at banks) fall into that category, I don’t think they’re fundamentally different from the banking I can already do today. I know some people disagree—they think the openness of the ledger still means something important—but I tend to think that’s not that big a deal if you have to rely on centralized actors again.” [↩]

- Several of the “rebasing” tokens seem to be replicating the ‘Hayek Money‘ proposal from 2014. Whereas a number of the Seigniorage Shares projects frequently cite a paper authored by Robert Sams. Note: since rebase and Seigniorage Shares tokens do not custody any commercial bank-backed stablecoins, they may not be directly impacted by some of the proposed legislation. [↩]

- Silvergate’s total cryptocurrency-related USD balances were up $500 million (39% QOQ) as of Q3 2020. Note: the Silvergate Exchange Network (SEN) is administered and operated by a single entity and is not a distributed ledger (blockchain). [↩]

- There were several spikes for USDC beyond that amount, including one $24.1 billion spike on January 3, 2021. [↩]

- Tether Ltd is incorporated in Hong Kong and registered with FinCEN, but in searching the Wyoming’s banking regulator, Tether Ltd is currently not listed. To be registered as a U.S.-based MSB, typically Tether Ltd would have to have a license with one of the state banking departments. What this means is: Tether Ltd is a foreign business that has chosen to register with FinCEN but Wyoming does not require MSBs that deal in cryptocurrency to get a state license. So Tether Ltd is operating in Wyoming as a transmitter, but does not have a license. That does not mean that the foreign jurisdiction where they reside regulates them. Many jurisdictions lack any sort of MSB framework. For instance, Canada does not have licenses for MSBs. So a Canadian business that transmits money does not operate by a separate set of rules from any other business, unlike in the U.S. where the state banking departments put limits on what sorts of assets MSBs and transmitters can hold. [↩]

- There were several spikes for USDT beyond that amount, including one $211.3 billion spike on January 4, 2021. [↩]

- There is leverage in the traditional foreign exchange marketplace too. Statista has a relevant chart showing average daily turnover in the global FX market. [↩]

- One reviewer commented: “Credit is a huge part of the current monetary system. We would be wrong to ignore it when we talk about stablecoins, which are interconnected with the financial system. Stablecoin promoters who intend to disrupt this system often don’t understand the very system they are disrupting. For example, some issuers wouldn’t be able to answer how their stablecoins would account for potential inflation or deflation, how supply and demand for these coins would be stabilized, or what happens during a crisis. This also ties back to an understanding of interest rates, which is so often lacking among stablecoin disrupters and is an integral part of the current system. [↩]

- Note: one of the common misconceptions of the STABLE Act is that stablecoin issuers would necessarily have to get a bank charter but the language of the actual bill provides lots of flexibility to regulators. [↩]

- We do not want to conflate velocity with TVL or rehypothecation either. Without the ability to see an exchanges books, the leverage facilitated by on-chain lending protocols is likely a magnitude order less than the leverage provided by off-chain exchanges. [↩]

- One reviewer commented: “The rapid growth in DeFi is directly correlated with the developments of the current generation of stablecoins, and this has been used to justify DeFi’s current value proposition. As a result, I do not see that as a sustainable way to create real value because of the dependency on these types of stablecoins. Programmable money and programmable assets is where the real innovation is and ideally neither should be reliant on pegged coins.” [↩]

- In other words: if large portions of “DeFi” applications rely on USDC or USDT, arguably this is incompatible with cypherpunkism or the decentralize-all-the-things meme. [↩]

- One reviewer noted that: “Cryptocurrency, like Bitcoin, was supposed to be sui generis. But if you peg or wrap to a fiat currency you are going to fall into regulatory problems. Even if DAI itself was just cryptocollateral they have a human-run governance mechanism and it is pegged to the dollar so it could fall under Securities law or Exchange regulations. If DAI remained entirely crypto, would be less problematic.” [↩]

- Maker maintains a public forum in which new types of collateral are proposed and voted on. [↩]

- In contrast, RAI only uses ETH as collateral and Seigniorage Shares is re-based solely on endogenous info. It is arguably hard to do but using endogenous data from the chain itself to rebase the coin value leads to a more resilient app and system (e.g. hard to switch off). [↩]

- Coin promoters – some of whom call themselves as cypherpunks – can ignore whatever regulations they want but that doesn’t prevent regulators and law enforcement from attempting to regulate and enforce activities in their remit. Over time the modus operandi of some coin promoters has shifted away from an endogenous engineering effort: ‘we have built an anti-fragile sovereign network and exited, so who cares what the government does.’ It has shifted towards an exogenous model, wherein coin promoters ask their followers to write to policy makers and donate to coin lobbyists because a popular “dApp” relies on something that the government regulates. [↩]

- Friedman LLP was the most recent auditor and they publicly walked away from Tether Ltd in 2018. See also research from professor John Griffin. [↩]

- One germane social media comment: “Stablecoins are IOUs with collateral in state-issued money. You can not expect non-intervention from State if you peg your asset to money issued from State. Stablecoins are Statecoins.” Another said: “If your coin is pegged to the USD, I don’t think you’re sticking it to The Man quite as much as you think you are.” [↩]

- Felix Salmon arguably had the most adroit take on the pushback against the STABLE Act. [↩]

- Another example: during the summer of 2014, rumors circulated that the BitLicense was about to be enacted (it wasn’t until the following year). During one of these periods, billionaire Tim Draper and his son, Adam, hosted a public meetup at their “university” in San Mateo. Multiple speakers repeated the same erroneous claims that the license would stymie “innovation.” Another memorable exchange was an reddit AMA with Ben Lawsky (then-Superintendent of Financial Services and architect of the BitLicense) in which the word “innovation” was flung around a lot as well. [↩]

- Executives from overseas cryptocurrency exchanges used to tell investors and potential investors that they had submitted paperwork to receive a BitLicense. This “impressive feat” was meant to show how “legit” the exchange was. One story involved Bobby Lee, then the CEO of BTC China, telling potential investors in the U.S. that BTC China had filed the paperwork with DFS. But what was left unsaid was that the application was mostly left blank and may actually have never been sent at all. [↩]

- Following the WSJ exposé, ShapeShift implemented identification checks for all trading activity. [↩]

- Note: I did say something similar to that on stage at the American Banker event. It was a panel that included Barry Silbert, who coincidentally was helping ShapeShift fundraise the next round at that time. It was the only panel whose video was not published online because not all of the panelists would give A/V permission to do so. The funding round was announced two months later. [↩]

- Payward Inc is d/b/a Kraken. It is registered with FinCEN as a MSB and has licenses in more than 50 territories and states. Strangely, Kraken’s Chief Legal Officer – Marco Santori – recently said Kraken is not a MSB: “Kraken is not a money transmitter. We haven’t sought licenses in the U.S. This is an alternative path to that, speaking purely from the regulatory perspective. The SPDI charter will help us to satisfy those rules as we seek to bring more and more of the payments flow in-house.” Technically speaking, a MTL is a subset of the MSB but unclear what that means in the context of Kraken or Tether Ltd. [↩]

- One of Kraken’s vocal investors, Caitlin Long, lobbied on their behalf in Wyoming and helped them gain approval for an SPDI. It will be interesting to see which bank(s) in New York handle the correspondence wiring between the two states. [↩]

- Dozens, perhaps a couple hundred, ICOs have registered in Singapore. The accommodative stance from MAS stems in part due to political influence from senior leaders, some of whom are believed to own ICO tokens. [↩]

- One reviewer commented: “It is probably too extreme to requires cryptocurrency exchanges and stablecoin issuers to become licensed banks. I think exchanges and stablecoin issuers that don’t deal with retail investors should be allowed to do what they like on the understanding that if they get into trouble, they will have no help whatsoever from the Fed Reserve or the U.S. government. But exchanges and stablecoin issuers that take retail deposits must be licensed and subject to banking regulation, and there may also need to be legislation to enforce structural separation of retail deposit-taking from crypto trading – something like a modern Glass-Steagall Act.” [↩]

- Technically speaking Visa is a card association that provides products to intermediaries, including access to VisaNet. Visa directly competes with China UnionPay and Mastercard. They operate tangentially to Square or Stripe who operate payment gateways on behalf of merchants. In his debate hosted by The Block, Jeremy Allaire conflated USDC issuance with activity on PayPal and Venmo. This is apples-to-oranges because USDC issuance and redemption happens at the very edge. And unlike PayPal and Venmo (who can continuously surveil internal accounts), USDC via Centre cannot on Ethereum. In fact, PayPal will not allow cryptocurrency-related transfers because the organization would be unable to comply with the “Travel Rule” or other FinCEN reporting requirements which by definition would mean USDC operates under a less strict framework relative to commercial banks. Note: other brokers such as Robinhood, Sofi, and Webull also do not allow users to transfer coins. [↩]

- There is some irony in how proof-of-work (P-o-W) chains have evolved. Initially P-o-W was used because Satoshi wanted to make Sybil attacks expensive in an adversarial environment with unknown participants including governments. Over time, as the dependency on U.S. and E.U. banks has grown, many promoters are now stating that governments better not (properly) regulate commercial bank backed-tokens despite some of these same promoters linking their KYC’ed wallets to other intermediaries. In theory, anarchic chains maneuver around The Man, by decentralizing and pseudonymizing the set of parties responsible for processing transactions. But in practice, most activity — more than 80% — still takes place between trusted intermediaries. [↩]

- From a systemic standpoint holding specific parties (issuers) responsible for activities they permitted (or were involved in) is a positive development. Why? Because, like banks or even payment processors, stablecoin issuers would have to monitor malignant behavior more closely than it does today. [↩]

- For perspective, at the state level there are MSB and/or MTO licenses that the entity such as a cryptocurrency exchange has to apply for. A couple of states don’t license this activity, hence why a few large cryptocurrency exchanges have 47 or 48 licenses. At the federal level the entity also registers with FinCEN (and then complies with the BSA). [↩]

- I wrote the most widely cited paper on “permissioned chains,” the creation of which was spurred by the inability of P-o-W chains to provide settlement finality or meet other requirements of the PFMIs. [↩]

- One of the problems with “enterprise”-focused blockchains or distributed ledgers is that they often introduce a single-point-of-trust (SPOT) which reduces their resiliency and makes them a poor candidate as an FMI. See also: “B-words,” “Evolving Language: Decentralized Financial Market Infrastructure,” and “Decentralized Financial Market Infrastructures” (forthcoming). [↩]

- Bears mentioning that if any anarchic chain has to rely on exogenous legal or financial support then it is not sovereign or anarchic. For example, each day somewhere there are multiple courts around the world in which aggrieved parties sue one another because of activities involving cryptocurrencies. While some of the outcomes remain as judicial precedent, others could become codified as statutes by legislatures. In either case, the disputes are not being handled on-chain. This off-chain dispute handling is another example of the “parasitic” reliance that anarchic chains continue to have on exogenous legal systems. [↩]

- For example, Coin Center published an article scaremongering readers into thinking the STABLE Act would – among other allegations – criminalize node operators. Vocal maximalists did the same thing. Not only are these claims unfounded but neither of these groups are focused on consumer or taxpayer protections. Commercial entities involved in money transmission, payment services, and/or using financial market infrastructure have to comply with a sundry of requirements in each jurisdiction they operate in. Irrespective of how mining nodes or non-mining nodes are categorized in the U.S. (or elsewhere), a “sufficiently decentralized” network should be resilient in an adversarial environment, including one with State-sponsored law enforcement snooping around. No one but faux “crypto lawyers” are talking about outlawing anonymous ledgers or chains. In other words, non-neutral critics are dwelling on remote edge cases that are outside the Overton Window. No law enforcement is going to go door to door searching for a Raspberry Pi node. [↩]

- One reviewer explained: “At both the state and federal level, governmental bodies in the U.S. have done a lot of heavy lifting and diligence to understand the cryptoasset and blockchain space. They have given it space to grow and develop, much more so than other innovations like drone deliveries which are just now being approved. For instance, the SEC created FinHub in 2018 which has its own permanent office; and in 2020 the SEC released a safe harbor proposal for special purpose broker dealers for custody of digital assets. If U.S. regulators wanted to kill the cryptoasset space, they could always go to the extent of cutting the cables, and destroying the servers, or using physical force and throwing everyone involved in jail, but what they have done was the opposite. It may have taken a couple of years to build capabilities and get it right, but they have devoted real resources and staff to make sure they understand what cryptoassets and blockchains are.” [↩]

- According to a recent article from Politico, the Office of Terrorism and Financial Intelligence is one of the few areas at Treasury under Secretary Mnuchin that has seen a resource bump. This trend could continue under the Biden administration as the recently passed NDAA included provisions (Section 6102) to enhance FinCEN’s capabilities and widen the definition of what a financial institution and money service transmitter are to broadly include other entities such as all virtual asset service providers (VASPs). [↩]

- A savvy prosecutor could probably make an easier case for why a mining pool / block maker is legally liable for say, knowingly processing ransomware payments because they are the “issuers” of coins. Whereas it may be harder to build a case against a vanilla non-mining node operator who merely performs non-administrative tasks. [↩]

- Run-of-the-mill “validating” nodes are not equivalent to actual miners who process transactions and build blocks. Without re-earthing the multitudinal debates around UASF / SegWit2x circa 2016-2017, mining pools are objectively in a different league. Non-mining nodes are often (but not always) overstated in importance on anarchic chains. With Deadcoins.com as evidence, proof-of-work chains live and die by miner participation. [↩]