[Note: I neither own nor have any trading position on any cryptocurrency. I was not compensated by any party to write this. The views expressed below are solely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of my employer or any organization I advise. See Post Oak Labs for more information.]

Alternative title: who will be the Harry Markopolos of cryptocurrencies?

If you don’t know who Harry Markopolos is, quickly google his name and come back to this article. If you do, and you aren’t completely familiar with the relevance he has to the cryptocurrency world, let’s start with a little history.

Background

Don’t drink the Koolaid

With its passion and perma-excitement, the cryptocurrency community sometimes deludes itself into thinking that it is a self-regulating market that doesn’t need (or isn’t subject to) government intervention to weed out bad actors. “Self-regulation,” usually refers to an abstract notion that bad actors will eventually be removed by the action of market forces, invisible hand, etc.

Yet by most measures, many bad actors have not left because there are no real consequences or repercussions for being a bad dude (or dudette).

Simultaneously, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars raised by VCs and over a couple billion dollars raised through ICOs in the past year or so, not one entity has been created by the community with the power or moral authority to rid the space of bad apples and criminals. Where is the regulatory equivalent of FINRA for cryptocurrencies?

Part of this is because some elements in the community tacitly enable bad actors. This is done, in some cases, by providing the getaway cars (coin mixers) but also, in other cases, with a wink and a nod as much of the original Bitcoin infrastructure was set-up and co-opted by Bitcoiners themselves, some of whom were bad actors from day one.

There are many examples, including The DAO. But the SEC already did a good dressing down of The DAO, so let’s look at BTC-e.

BTC-e is a major Europe-based exchange that has allegedly laundered billions of USD over the span of the past 6 years. Its alleged operator, Alexander Vinnik, stands accused of receiving and laundering some of the ill-gotten gains from one of the Mt. Gox hacks (it was hacked many many times) through BTC-e and even Mt. Gox itself. BTC-e would later go on to be a favorite place for ransomware authors to liquidate the ransoms of data kidnapping victims.

Who shut down BTC-e?

It wasn’t the enterprising efforts of the cryptocurrency community or its verbose opinion-makers on social media or the “new 1%.” It was several government law enforcement agencies that coordinated across multiple jurisdictions on limited budgets. Yet, like Silk Road, some people in the cryptocurrency community likely knew the operators of the BTC-e and willingly turned a blind eye to serious misconduct which, for so long as it continues, represents a black mark to the entire industry.

In other cases, some entrepreneurs and investors in this space make extraordinary claims without providing extraordinary evidence. Such as, using cryptocurrency networks are cheaper to send money overseas than Western Union. No, it probably is not, for reasons outlined by SaveOnSend.

But those who make these unfounded, feel-good claims are not held accountable or fact-checked by the market because many market participants are solely interested in the value of coins appreciating. Anything is fair game so as long as prices go up-and-to-the-right, even if it means hiring a troll army or two to influence market sentiment.

And yet in other cases, the focus of several industry trade associations and lobbying groups is to squarely push back against additional regulations and/or enforcement of existing regulations or PR that contradicts their narrative.

Below are eight suggested areas for further investigation within this active space (there could be more, but let’s start with this small handful):

(1) Bitfinex

Bitfinex is a Hong Kong-based cryptocurrency exchange that has been hacked multiple times. Most recently, about 400 days ago, $65 million dollars’ worth of bitcoins were stolen.

Bitfinex is a Hong Kong-based cryptocurrency exchange that has been hacked multiple times. Most recently, about 400 days ago, $65 million dollars’ worth of bitcoins were stolen.

Bitfinex eventually painted over these large losses by stealing from its own users, by socializing the deficits that took place in some accounts across nearly all user accounts. Bitfinex has – despite promising public audits and explanations of what happened – provided no details about how it was hacked, who hacked it, or to where those funds were drained to. It has also self-issued at least two tokens (BFX and RRT) representing their debt and equity to users, listed these tokens on their own exchange and allowed their users to trade them.

There have been suggestions of impropriety, with its CFO (or CSO?) Phil Potter publicly explaining how they handle being de-banked and re-banked:

“We’ve had banking hiccups in the past, we’ve just always been able to route around it or deal with it, open up new accounts, or what have you… shift to a new corporate entity, lots of cat and mouse tricks that everyone in Bitcoin industry has to avail themselves of.”

Yet there is little action by the cryptocurrency community to seek answers to the open questions surrounding Bitfinex. I wrote a detailed post several months ago on it and the only reporters who contacted me for follow-ups were from mainstream press.

There are a lot of reasons why, but one major reason could be that some customers have financially benefited from this lack of market surveillance because relatively little KYC (Know Your Customer) is collected or AML (Anti-Money Laundering) enforced, so some trades and/or taxes are probably unreported. This wouldn’t be an isolated incident as the IRS has said less than 1,000 United States persons have been filing taxes related to “virtual currencies” each year between 2013 – 2015.

But that’s not all.

The latest series of drama began earlier this spring: Bitfinex sued Wells Fargo who had been providing correspondent banking access to Bitfinex’s Taiwanese banking partners. Wells Fargo ended this relationship which consequently tied up tens of millions of USD that was being wired internationally on behalf of Bitfinex’s users. About a week later Bitfinex dropped the suit and at least one person involved on the compliance side of a large Taiwanese bank was terminated due to the misrepresentation of the Bitfinex account relationship.

This also impacted the price of Tether.

Tether, as its name suggests, is a proprietary cryptocurrency (USDT) that is “always backed by traditional currency held in our reserves.” It initially used a cryptocurrency platform called Mastercoin (rebranded to Omni) and recently announced an ERC20 token on top of Ethereum.

As a corporate entity, Tether’s governance, management, and business are fairly opaque. No faces or names of employees or personnel can be found on its site. Bitfinex was not only one of its first partners but is also a shareholder. Bitfinex has also created a new ICO trading platform called Ethfinex and just announced that Tether will be partnering with it in some manner.

Tether as an organization creates coins. These coins are known as Tethers that trade under the ticker $USDT each of which, as is claimed on their webpage, is directly linked, 1-for-1, with USD and yen equivalents deposited in commercial banks. But after the Wells Fargo suit was announced, USDT “broke the buck” and traded at $0.92 on the dollar. It has fluctuated a great deal during the summer currently trades at $1.00 flat.

Which leads to the question: are the seven banks listed by the recent CPA disclosure aware of what Tether publicly advertises its USDT product as?

Who is responsible for issuance, and how if at all can they be redeemed? Are they truly backed 1:1 or is there some accounting sleight-of-hand taking place behind the scenes? Where are those reserves going to be exactly? Who will have access to them? Will either Tether (the company) or Bitfinex going to use them to trade? These are the types of questions that should be asked and publicly answered.

The only reason anyone is learning anything about the project is because of an anonymous Tweeter, going by the handle @Bitfinexed, who seemingly has nothing better to do than listen to hundreds of hours of audio archives of Bitcoiners openly bragging about their day trading schemes and financial markets acumen (in that order).

Despite myself and others having urged coin media to do so, to my knowledge there have been no serious investigations or transparency as to who owns or runs this organization. Privately, some reporters have blamed a lack of resources for why they don’t pursue these leads; this is odd given the deluge of articles posted every month on the perpetual block size debate that will likely resolve itself in the passage of time.

The only (superficial) things we know about Tether (formerly Realcoin) is from the few bits of press releases over time. Perhaps this is all just a misunderstanding due to miscommunication. Who wants to fly to Hong Kong and/or Taiwan to find out more?

(2) Ransomware, Ponzi’s, Zero-fee and AML-less exchanges

Last month a report from Xinhua found that:

China’s two biggest bitcoin exchanges, Huobi and OKCoin, collectively invested around 1 billion yuan ($150 million) of idle client funds into “wealth-management products.”

In other words, the reason these exchanges were able to operate and survive while charging zero-fees is partially offset by these exchanges using customer deposits to invest in other financial products, without disclosing this to customers.

Based on conversations with investigative reporters and former insiders, it appears that many, if not most, mid-to-large exchanges in China used customer deposits (without disclosing this fact) to purchase other financial products. It was not just OKCoin and Huobi but also BTCC (formerly BTC China) and others. This is not a new story (Arthur Hayes first wrote about it in November 2015), but the absence of transparency in how these exchanges and intermediaries are run ties in with what we have seen at BTC-e. While there were likely a number of legitimate, non-illicit users of BTC-e (like this one Australian guy), the old running joke within the community is that hackers do not attack BTC-e because it was the best place to launder their proceeds.

Many exchanges, especially those in developing countries lacking KYC and AML processes, directly benefited from thefts and scams. Yet we’ve seen very little condemnation from the main cheerleaders in the community.

For example, two years ago in South Africa, MMM’s local chapter routed around the regulated exchange, patronizing a new exchange that wouldn’t block their transactions. MMM is a Ponzi scheme that has operated off-and-on for more than twenty years in dozens of countries. In its most current incarnation it has raised and liquidated its earnings via bitcoin. As a result, the volume on the new exchange in South Africa outpaced the others that remained compliant with AML procedures. Through coordination with law enforcement it was driven out for some time, but in January of this year, MMM rebooted and it is now reportedly back in South Africa and Nigeria. The same phenomenon has occurred in multiple other countries including China, wherein, according to inside sources, at least one of the Big 3 exchanges gave MMM representatives the VIP treatment because it boosted their volume.

It was a lack of this market surveillance and customer protections and outright fraud that eventually led to many of the Chinese exchanges being investigated and others raided by local and national regulators in a coordinated effort during early January and February 2017.

Initially several executives at the non-compliant exchanges told coin media that nothing was happening, that all the rumors of investigation was “FUD” (fear, uncertainty, doubt). But they were lying.

Regulators had really sent on-site staff to “spot check” and clean up the domestic KYC issues at exchanges. They combed through the accounting books, bank accounts, and trading databases, logging the areas of non-compliance and fraud. This included problems such as allowing wash-trading to occur and unclear margin trading terms and practices. Law enforcement showed these problems (in writing) to exchange operators who had to sign and acknowledge guilt: that these issues were their responsibility and that there could be future penalties.

Following the recent government ban on ICO fundraising (described in the next section), all exchanges in China involved in fiat-to-cryptocurrency trades have announced they will close in the coming weeks, including Yunbi, an exchange that was popular with ICO issuers. On September 14th, the largest exchange in Shanghai, BTCC (formerly BTC China), announced it would be closing its domestic exchange by the end of the month. It is widely believed it was required to do so for a number of compliance violations and for having issued and listed an ICO called ICOCoin.

Source: Tweet from Linke Yang, co-founder of BTCC

The two other large exchanges, OKCoin and Huobi, both announced on September 15th that they will be winding down their domestic exchange by October 31st. Although according to sources, some exchange operators hope this enforcement decision (to close down) made by regulators will quietly be forgotten after the Party Congress ends next month.

One Plan B is a type of Shanzhai (山寨) hawala which has already sprung up on Alibaba whereby users purchase discrete units of funds as a voucher from foreign exchanges (e.g., $1,000 worth of BTC at a US-based exchange). Many exchanges are trying to setup offices and bank accounts nearby in Hong Kong, South Korea, and Japan, however this will not solve their ability to fund RMB-denominated trades.

It is still unclear at this time what the exact breakdown in areas of non-compliance were largest (or smallest). For instance, how common was it to use a Chinese exchange for liquidating ransomware payments?

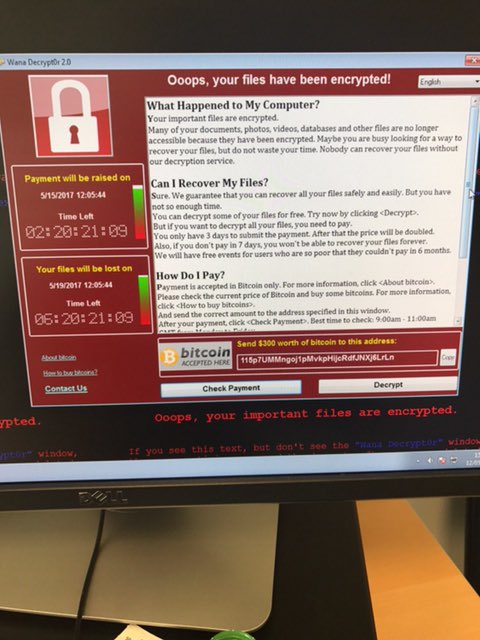

As mentioned in an earlier post, cryptocurrencies are the preferred payment method for ransomware today because of their inherent characteristics and difficulty to reclaim or extract recourse. One recent estimate from Cybersecurity Ventures is that “[r]ansomware damage costs will exceed $5 billion in 2017, up more than 15X from 2015.” The victims span all walks of life, including the most at-risk and those providing essential services to the public (like hospitals).

But if you bring up this direct risk to the community, be prepared to be shunned or given the “whataboutism” excuse: sure bitcoin-denominated payments are popular with ransomware, but whatabout dirty filthy statist fiat and the nuclear wars it funds!

Through the use of data matching and analytics, there are potential solutions to these chain of custody problems outlined later in section 8.

(3) Initial coin offerings (ICOs)

Obligatory South Park reference (Credit: Jake Smith)

Irrespective of where your company is based, the fundraising system in developed – let alone developing countries – is often is a time consuming pain in the rear. The opportunity costs foregone by the executive team that has to road show is often called a necessary evil.

There has to be a more accessible way, right? Wouldn’t it just be easier to crowdfund from (retail) investors around the world by selling or exchanging cryptocurrencies directly to them and use this pool of capital to fund future development?

Enter the ICO.

In order to participate in a typical ICO, a user (and/or investor) typically needs to acquire some bitcoin (BTC) or ether (ETH) from a cryptocurrency exchange. These coins are then sent to a wallet address controlled by the ICO organizer who sometimes converts them into fiat currencies (often without any AML controls in place), and sends the user/investor the ICO coin.

Often times, ICO organizers will have a private sale prior to the public ICO, this is called a pre-sale or pre-ICO sale. And investors in these pre-sales often get to acquire tokens at substantial discounts (10 – 60%) than the rate public investors are offered.. ICO organizers typically do not disclose what these discounts are and often have no vesting cliffs attached to them either.

The surge in popularity of ICOs as a way to quickly exploit and raise funds (coins) and liquidate them on secondary markets has transitively led to a rise in demand of bitcoin, ether, and several other cryptocurrencies. Because the supply of most of the cryptocurrencies is perfectly inelastic, any significant increase (or decrease) in demand can only be reflected via volatility in prices.

Hence, ICOs are one of the major contributing factors as to why we have seen record high prices of many different cryptocurrencies that are used as gateway coins into ICOs themselves.

According to one estimate from Coin Schedule, about $2.1 billion has been raised around the world for 140 different ICOs this year. My personal view is that based on the research I have done, most ICO projects have intentionally or unintentionally created a security and are trying to sell it to the public without complying with securities laws. Depending on the jurisdiction, there may be a small handful of others that possibly-kinda-sorta have created a new coin that complies with existing regs. Maybe.

Ignoring the legal implications and where each fits on that spectrum for the moment, many ICOs to-date have pandered to and exploited terms like “financial inclusion” when it best suits them. Others pursue the well-worn path of virtue signaling: Bitcoiners condemning the Ethereum community (which itself was crowdfunded as an ICO), because of the popularity in using the Ethereum network for many ICOs… yet not equally condemning illicit fundraising that involves bitcoin or the Bitcoin network or setting up bucket shops such as Sand Hill Exchange (strangely one of its founders who was sued by the SEC now writes at Bloomberg).

The cryptocurrency community as a whole condemned the “Chinese government” for its recent blanket ban on fundraising and secondary market listing of ICOs. The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) is one of seven regulators to enforce these regulations yet most of the public antagonism has been channeled at just the PBOC.

Irrespective of whether you think it was the right or wrong thing to do because you heart blockchains, the PBOC and other regulators had quite valid reasons to do so: some ICO creators and trading platforms were taking funds they received from their ICO and then re-investing those into other ICOs, who in turn invested in other ICOs, and so forth; creating a fund of fund of funds all without disclosing it to the public or original investors. ICO Inception (don’t tell Christopher Nolan).

In China and in South Korea, and several other countries including the US, there is a new cottage industry made of up entities called “community managers” (CM) wherein an ICO project hires an external company (a CM) who provides a number of services:

- for X amount of BTC the CM will actively solicit and get your coin listed on various exchanges;

- the CM takes a sales commission while marketing the coin to the public such that after the ICO occurred, they would take a juicy cut of the proceeds; and several other promotional services.

The ICO issuers and fundraising/marketing teams usually organize a bunch of ICOs weekly and typically employ a market maker (known as an “MM” in the groups) whose role is to literally pump and dump the coin. They engage in ‘test pumps’ and ‘shakeouts’ to get rid of the larger ICO investors so they can push the price up on a thin order book by 10x, 20x, or 30x before distributing and pulling support. You can hire the services of one of these traders in many of the cryptocurrency trading chat groups.

There were even ICO boot camps (训练营) in China (and elsewhere) usually setup with shady figures with prior experience in pyramid schemes. Here they coached the average person to launch an ICO on the fly based on the ideas of this leader to people of all demographics including the vulnerable and at-risk. Based on investigations which are still ongoing, the fraud and deceit involved was not just one or two isolated incidents, it was rampant. Obtaining the training literature that was given to them (e.g., the script with the promises made) would make for a good documentary and/or movie.

In other words, the ICO rackets have recreated many aspects of the financial services industry (underwriters, broker/dealers) but without any public disclosures, organizational transparency, investor protections, or financial controls. Much like boiler rooms of days past. It is no wonder that with all of this tomfoolery, according to Chainalysis, that at least $225 million worth of ETH has been stolen from ICO-related fundraising activity this past year.

At its dizzying heights, in China, there were about sixty ICO crowdfunding platforms each launching (or trying to launch) new ICOs on a monthly basis. And many of these platforms also ran and operated their own exchanges where insiders were pumping (and dumping) and seeing returns of up to 100x on coins that represented “social experiments to test human stupidity” such as the performance art pictured below.

One recent estimate from Reuters was that in China, “[m]ore than 100,000 investors acquired new cryptocurrencies through 65 ICOs in January-June [2017].” It’s still unclear what the final straw was, but the universal rule of don’t-pitch-high-risk-investment-schemes-to-grandmothers-on-fixed-incomes was definitely breached.

As a result, the PBOC and other government entities in China are now disgorging any funds (about $400 million) that ICOs had raised in China. This number could be higher or lower depending on how much rehypothecation has taken place (e.g., ICOs investing in ICOs). All crowdfunding platforms such as ICOAGE and ICO.info have suspended operations and many have shut down their websites. In addition, several executives from these exchanges have been given a travel ban.

Cryptocurrency exchanges (the ones that predated the ICO platforms) have to delist ICOs and freeze plans from adding any more at this time. Multiple ICO promotional events, including those by the Fintech Blockchain Group (a domestic fund that organized, promoted, and invested in ICOs) have been canceled due to the new ban. Several well-known promoters have “gone fishing” overseas. This past week, Li Xiaolai, an early Bitcoin investor and active ICO promoter, has publicly admitted to having taken the ICO mania too far (using a car acceleration example), an admission many link to the timing of this crackdown and ban.

A real ICO in China: “Performance Art Based on Block Chain Technology” (Source)

For journalists, keep in mind this is (mostly) just one country described above. It would be a mistake to pin all of the blame on just the ICO operators based in China as similar craziness is happening throughout the rest of the world (observe the self-serving celebrity endorsements). Be sure to look at not just the executives involved in an ICO but also the advisors, investors, figureheads, and anyone who is considered “serious” lending credibility to dodgy outfits and dragging the average Joe (and Zhou) and his fixed income or meager savings into the game.

There may be a legitimate, legal way of structuring an ICO without running afoul of helpful regulations, but so far those are few and far between. Similarly, not everyone involved in an ICO is a scammer but it’s more than a few bad apples, more like a bad orchard. And as shown above with the initial enforcement actions of just one country, short sighted hustling by unsavory get-rich-quick partisans unfortunately might deep-six the opportunities for non-scammy organizations and entrepreneurs to utilize a compliant ICO model in the future.

(4) VC-backed entities

Theranos, Juicero, and Hampton Creek, meet Coinbase, 21.co, Blockstream, and several others.

Okay, so that may be a little exaggerated. But still the same, few high-profile Bitcoin companies are publishing daily active or monthly active user numbers for a variety of reasons.

Founded in May 2012, the only known unicorn to-date is Coinbase. Historically it has kept traction stats close to the chest but we got a small glimpse at what Coinbase’s user base was from an on-going lawsuit with the IRS. According to one filing, between 2013-2015 (the most recent publicly available data) Coinbase had around 500,000 users, of which approximately 14,355 accounts conducted at least $20,000 in business. This is a far cry from the millions of wallets we saw as a vanity statistic prominently displayed on its homepage during that same time period.

What did most users typically do? They created an account, bought a little bitcoin, and then hoarded it – very few spent it as if it were actual money which is one of the reasons why they removed a publicly viewable transaction chart over a year ago.

To be fair, the recent surge in market prices for cryptocurrencies has likely resulted in huge user growth. In fact, Coinbase’s CEO noted that 40,000 new users signed up on one day this past May. But some of this is probably attributed to new users using Coinbase as an on-and-off ramp: United States residents acquiring bitcoin and ether on Coinbase and then participating in ICOs elsewhere.

After more than $120 million in funding, 21.co (formerly 21e6) has not only seen an entire executive team churn, but a huge pivot from building hardware (Bitcoin mining equipment) into software and now into a pay-as-you-go-LinkedIn-but-with-Bitcoin messaging service. Launched with much fanfare in November 2015, the $400 Amazon-exclusive 21.co Bitcoin Computer was supposed to “return economic power to the individual.”

In reality it was just a USB mining device (a Raspberry Pi cobbled together with an obsolete mining chip) and was about as costly and useful as the Juicero juicing machine. It was nicknamed the “PiTato” and unit sales were never publicly disclosed. Its story is not over: in the process of writing this article, 21.co announced it will be launching a “social token” (SOC) by the end of the year.

Blockstream is the youngest of the trio. Yet, after three years of existence and having raised at least $76 million, as far as the public can tell, the company has yet to ship a commercial product beyond an off-the-shelf hardware product (Liquid) that generates a little over $1 million in revenue a year. It also recently launched a satellite Bitcoin node initiative it borrowed from Jeff Garzik, who conceived it on a budget of almost nothing about three years ago.

To be fair though, perhaps it does not have KPIs like other tech companies. For instance, about two and half years ago, one of their largest investors, Reid Hoffman, said Blockstream would “function similarly to the Mozilla Corporation” (the Mozilla Corporation is owned by a nonprofit entity, the Mozilla Foundation). He likened this investment into “Bitcoin Core” (a term he used six times) as a way of “prioritiz[ing] public good over returns to investors.” So perhaps expectations of product roadmaps is not applicable.

On the flipside, some entrepreneurs have explained that their preference for total secrecy is not necessary because they are afraid of competition (that is a typical rationale of regular startups), but because they are afraid of regulators via banks. For example, a regulator sees a large revenue number, finds out which bank provides a correspondent service and if the startup is fully compliant with AML, CFT, and KYC processes, starts auditing that bank, and banks re-evaluates NPV of working with a startup and potentially drops it. Until that changes, we will not know volumes for Abra, Rebit, Luno, and others and that is why a year-old claim about 20% market share in the South Korea -> Philippines remittance corridor remains evidence-free.

While we would all love to see more data, this is a somewhat believable argument. A more insightful question might be if/when we get to a point where supporting Bitcoin players becomes enough of real revenue that banks would agree to higher investments and support. In the meantime, business journalists should drill down into the specifics about how raised money has been spent, is compliance being skirted, customer acquisition costs, customer retention rate, etc.

(5) The decline of Maximalism

If you were to draw a Venn diagram, where one circle represented neo Luddism and another circle represented Goldbugism, the areas they overlap would be cryptocurrency Maximalism (geocentrism and all). This increasingly smaller sect, within the broader cryptocurrency community, believes in a couple of common tenets but most importantly: that only one chain or ledger or coin will rule them all. This includes the Ethereum Classic (ETC) and Bitcoin Core sects, among others.

They’re a bit like the fundamentalists in that classic Monty Python “splitters” sketch but not nearly as funny.

If you’re looking to dig into defining modern irony, these are definitely the groups to interview. For instance, on the one hand they want and believe their Chosen One (typically BTC or ETC) should and will consume the purchasing power of all fiat currencies, yet they dislike any competing cryptocurrency: it is us versus them, co-existence is not an option! The rules of free entry do not apply to their coin as somehow a government-free monopoly will form around their coin and only their coin. Also, you should buy a lot of their coin, like liquidate your life savings asap and buy it now.

Artist rendering of proto-Bitcoin Maximalism, circa 14th century

This rigidity has diminished over time.

Whereas, three years ago, most active venture capitalists and entrepreneurs involved in this space were antagonistic towards anything but bitcoin, more and more have become less hostile with respect to new and different platforms.

For instance, Brian Armstrong (above), the CEO of Coinbase, two and a half years ago, was publicly opposed to supporting development activities towards anything unrelated to Bitcoin.

But as the adoption winds shifted and Ethereum and other platforms began to see growth in their development communities (and coin values), Coinbase and other early bastions of maximalism began to support them as well.

Source: Twitter (1 2)

There will likely be permanent ideological holdouts, but as of this writing I would guesstimate that less than 20% of the bitcoin holders I have interacted with over the past 6-9 months would label themselves maximalists (the remaining would likely self-identify with the “UASF” and “no2x” tags on Twitter).

So interview them and get their oral history before they go extinct!

(6) Market caps

There is very little publicly available analysis of what is happening with Bitcoin transactions (or nearly all cryptocurrencies for that matter): dormant vs. active, customers vs. accounts, transaction types (self-transfers vs. remittances vs. B2B, etc.).

On-chain transaction growth seems to be slowing down on the Bitcoin network and we don’t have good public insights on what is going on: are there are pockets of growth in real adoption or just more wallet shuffling?

In other words, someone should be independently updating “Slicing data” but instead all we pretty much see is memes of Jamie Dimon or animated gifs involving roller coaster prices.

In the real world, “market cap” is based on a claim on a company’s assets and future cash flows. Bitcoin (and other cryptocurrencies) has neither — it doesn’t have a “market cap” any more than does the pile of old discarded toys in your garage.

“Market Cap” is a really dumb phrase when applied to the cryptocurrency world; it seems like one of those seemingly straightforward concepts ported to the cryptocurrency world directly from mainstream finance, yet in our context it turns into something misleading and overly simplistic, but many day traders in this space who religiously tweet about price action love to quote.

The cryptocurrency “market cap” metric is naively simplistic: take the total coin supply, and multiply it by the current market price, and voila! Suddenly Bitcoin is now approaching the market cap of Goldman Sachs!

Yeah, no.

To begin with, probably around 25% or more of all private keys corresponding to bitcoins (and other cryptocurrencies too) have been permanently lost or destroyed. Most of these were from early on, when there was no market price and people deleted their hard drives with batches of 50 coins from early block rewards without backing them up or a second thought.

Extending this analogy, 25% of the shares in Goldman Sachs cannot suddenly become permanently ownerless. These shares are registered assets, not bearer assets. Someone identifiable owns them today and even if there is a system crash at the DTCC or some other CSD, shareholders have a system of recourse (i.e., the courts) to have these returned or reissued to them with our without a blockchain. Thus, anytime you hear about “the market price of Bitcoin has approached $XXX billion!” you should automatically discount it by at least 25%.

Also, while liquidity providers and market makers in Bitcoin have grown and matured (Circle’s OTC desk apparently trades $2 billion per month), this is still a relatively thinly traded market in aggregate. It is, therefore, unlikely that large trading positions could simultaneously move into and out of billion USD positions each day without significantly moving the market. A better metric to look at is one that involves real legwork to find: the average daily volume on fee-based, regulated spot exchanges combined with regulated OTC desks. That number probably exists, but no one quotes it. Barring this, an interim calculation could be based on “coins that are not lost or destroyed.”

(7) Buy-side analysts and coin media

We finally have some big-name media beginning to dig into the shenanigans in the space. But organizations like CoinDesk, Coin Telegraph, and others regularly practice a brand of biased reporting which primarily focus on the upside potential of coins and do not provide equal focus on the potential risks. In some cases, it could be argued that these organizations act as slightly more respectable conduits for misinformation churned out by interested companies.

Common misconceptions include continually pushing out stories like the example above, on “market caps” or covering vanity metrics such as growth in wallet numbers (as opposed to daily active users). It is often the case that writers for these publications are heavily invested in and/or own cryptocurrencies or projects mentioned in their stories without public disclosure.

This is not to say that writers, journalists, and staff at these organizations should not own a cryptocurrency, but they should publicly disclose any trading positions (including ‘hodling’ long) as the sentiment and information within their articles can have a material influence on the market prices of these coins.

For instance, CoinDesk is owned by Digital Currency Group (DCG) who in turn has funded 80-odd companies over the last few years, including about 10 mentioned in this article (such as Coinbase and BTC China). DCG also is an owner of a broker/dealer called Genesis Trading, an OTC desk which trades multiple cryptocurrencies that DCG and its staff, have publicly acknowledged at having positions in such as ETC, BTC and LTC.

What are the normal rules around a media company (and its staff) retweeting and promoting cryptocurrencies or ICOs the parent company or its principals has a stake in?

If coin media wants to be taken seriously it will have to take on the best practices and not appear to be a portfolio newsletter: divorce itself of conflicts of interest by removing cross ownership ties and prominently disclose all of the remaining potential conflicts of interest with respect to ownership stakes and coin holdings. Markets that transmit timely, accurate, and transparent information are better markets and are more likely to grow, see, and support longer-term capital inflows.

For example, if Filecoin is a security in the US (which its creators have said it is), and DCG is an equity holder in Filecoin/Protocol Labs (which it is)… and DCG is an owner in CoinDesk, what are the rules for retweeting this ICO above? There are currently 16 stories in the CoinDesk archive which mention Filecoin, including three that specifically discuss its ICO. Is this soliciting to the public?

Similarly, many of the buy-side analysts that were actively publishing analysis this past year didn’t disclose that they had active positions on the cryptocurrencies they covered. We recently found out that one lost $150,000 in bitcoins because someone hacked his phone.

At cryptocurrency events (and fintech events in general), we frequently hear buzz word bingo including: smart assets, tokens, resilience, pilots, immutability, even in-production developments, but there is often no clear articulation of what are the specific opportunities to save or make money for institutions if they acquire a cryptocurrency or uses its network to handle a large portion of their business.

This was the core point of a popular SaveOnSend article on remittances from several years ago. I recommend revisiting that piece as a model for similar in-depth assessments done by people who understand B2B payments, correspondent banking and other part of global transfers. Obviously this trickles into the other half of this space, the enterprise world which is being designed around specific functional and non-functional requirements, the SLAs, compliance with data privacy laws, etc., but that is a topic for another day.

What about Coin Telegraph? It is only good for its cartoon images.

Source: LinkedIn

There are some notable outliers that serve as good role models and exceptions to the existing pattern and who often write good copy. Examples of which can be found in long end note.

Obviously the end note below is non-exhaustive nor an endorsement, but someone should try to invite some or all these people above to an event, emceed by Taariq Lewis. That could be a good one.

(8) Analytics

What about solutions to the problems and opaqueness described throughout this article?

There are just a handful of startups that have been funded to create and use analytics to identify usage and user activity on cryptocurrency networks including: Chainalysis, Blockseer, Elliptic, WizSec, ScoreChain, Skry (acquired by Bloq) – but they are few and far between. Part of the reason is because the total addressable market is relatively small; the budgets from compliance departments and law enforcement is now growing but revenue opportunities were initially limited (same struggle that coin media has). Another is that the analytic entrepreneurs are routinely demonized by the same community that directly benefits from the optics they provide to exchanges in order to maintain their banking partnerships and account access.

Such startups are shunned today, unpopular and viewed as counter to the roots of (pseudo) anonymous cryptocurrencies, however, as regulation seeps into the industry an area that will gain greater attention is identification of usage and user activities.

For instance, four years ago, one article effectively killed a startup called Coin Validation because the community rallied (and still rallies) behind the white flag of anarchy, surrendering to a Luddite ideology instead of supporting commercial businesses that could help Bitcoin and related ideas and technologies comply with legal requirements and earn adoption by mainstream commercial businesses. For this reason, cryptocurrency fans should be very thankful these analytics companies exist.

Source: Twitter. Explanation: Wanna Cry ransomware money laundering with Bitcoins in action. Graph shows Bitcoin being converted to Monero (XMR) via ShapeShift.io

More of these analytics providers could provide even better optics into the flow of funds giving regulated institutions better handling of the risks such as the money laundering taking place throughout the entire chain of custody.

Without them, several large cryptocurrency exchanges would likely lose their banking partners entirely; this would reduce liquidity of many trading pairs around the world, leading to prices dropping substantially, and the community relying once again on fewer sources of liquidity run out of the brown bags on shady street corners.

One key slide from Kim Nilsson’s eye-opening presentation: Cracking MtGox

And perhaps there is no better illustration of how these analytic tools can help us understand the fusion of improper (or non-existent) financial controls plus cryptocurrencies: Mt. Gox. Grab some warm buttery popcorn and be sure to watch Kim Nilsson’s new presentation covering all of the hacks that this infamous Tokyo-based exchange had over its existence.

Journalists, it can be hard to find but the full order book information for many exchanges can be found with enough leg work. If anyone had the inclination to really want to understand what was going on at the exchange, there are 3rd parties which have a complete record of the order book and trades executed.

Remember, as Kim Nilsson and others have independently discovered, WillyBot turned out to be true.

Final Remarks

The empirical data and stories above do not mean that investors should stop trading all cryptocurrencies or pass on investing in blockchain-related products and services.

To the contrary, the goal of this article is to elevate awareness that this industry lacks even the most basic safeguards and independent voices that would typically act as a counterbalance against bad actors. In this FOMO atmosphere investors need to be on full alert of the inherent risks of a less than transparent market with less than accurate information from companies and even news specialists.

Cryptocurrencies aren’t inherently good or bad. In a single block, they can be used as a means to reward an entity for securing transactions and also a payment for holding data hostage.

One former insider at an exchange who reviewed this article summarized it as the following:

The cryptocurrency world is basically rediscovering a vast framework of securities and consumer protection laws that already exist; and now they know why they exist. The cryptocurrency community has created an environment where there are a lot of small users suffering diffuse negative outcomes (e.g., thefts, market losses, the eventual loss on ICO projects). And the enormous gains are extremely concentrated in the hands of a small group of often unaccountable insiders and “founders.” That type of environment, of fraudulent and deceptive outcomes, is exactly what consumer and investor protection laws were created for.

Generally speaking, most participants such as traders with an active heartbeat are making money as the cryptocurrency market goes through its current bull run, so no one has much motive to complain or dig deeper into usage and adoption statistics. Even those people who were hacked for over $100,000, or even $1 million USD aren’t too upset because they’re making even more than that on quick ICO returns.

We are still at the eff-you-money stage, in which everyone thinks they are Warren Buffett. The Madoffs will only be revealed during the next protracted downturn. So if you’re currently getting your cryptocurrency investment advice from permabull personalities on Youtube, LinkedIn, and Twitter with undisclosed positions and abnormally high like-to-comment ratios, you might eventually be a bag holder.

Like any industry, there are good and bad people at all of these companies. I’ve met tons of them at the roughly 100+ events and meetups I have attended over the past 3-4 years and I’d say that many of the people at the organizations above are genuinely good people who tolerate way too much drivel. I’m not the first person to highlight these issues or potential solutions. But I’m not a reporter, so I leave you with these leads.

While everyone waits for Harry Markopolos to come in and uncover more details of the messes in the sections above, other ripe areas worth digging into are the dime-a-dozen cryptocurrency-focused funds.

Future posts may look at the uncritical hype in other segments, including the enterprise blockchain world. What happened after the Great Pivot?

[Note: if you found this research note helpful, be sure to visit Post Oak Labs for more in the future.]

Acknowledgements

To protect the privacy of those who provided feedback, I have only included initials: JL, DH, AL, LL, GW, CP, PD, JR, RB, ES, MW, JK, RS, ZK, DM, SP, YK, RD, CM, BC, DY, JF, CK, VK, CH, HZ, and PB.

End notes

For background, this post assumes you have read some (or ideally all) of the previous posts:

For background, this post assumes you have read some (or ideally all) of the previous posts: