More than a couple of people have asked for an update to a popular post published 14 months ago.

What has changed?

Before we begin, a quick reminder: the basic security model behind proof-of-work (PoW) blockchains is to make it economically costly to successfully rewrite the chain’s history. Finite resources, whether it is in the form of electricity or semiconductors, have to be consumed.

Therefore, a PoW chain such as Bitcoin, cannot simultaneously be secure and inexpensive to operate. Because if it was inexpensive to operate it would also be inexpensive to successfully attack.

Bitcoin

For Bitcoin, Bitmain announced its S17e system which can churn out 64TH/s. Each machine consumes ~2880 watts at the wall. The first of these units are scheduled to be shipped to customers in November (however other less powerful variants shipped during the summer).

The current Bitcoin hashrate has been oscillating around 100 million TH/s the past few weeks.

[Source: Blockchain.info]

If the entire network was comprised of the unreleased S17e-based machines, there would be around 1.56 million of them. In a given year these would gulp down about 39.4 billion kWh. But we know that is not the case yet. Thus, this will serve as our lower bound.

Bitmain is also shipping several other newly released systems, including the T17e. Like its cousin above, the T17e also consumes about ~2880 at the wall. But it is not as efficient per hash: creating only 53 TH/s with the same amount of electricity.

Why manufacture and sell two (or more) different machines that draw roughly the same amount of power?

Cost. the T17e costs $1665 and the S17e is $2483. The target market for the T17e is supposedly for miners who have low or no electricity costs.

How many T17e’s would it take to generate the 100 million TH/s network hashrate? About 1.88 million; or an additional 300,000 more machines than the S17e.

A quick pause. these types of bulk purchases are not idle speculation. In the middle of last summer, during a two-week period of time, the equivalent of 100,000 mining machines was added to the Bitcoin network (likely early variants of the S17). This is a reversal from last November, wherein the equivalent of ~1.3 million S9s were taken offline during one month.

Again, we know that in practice that there are many more less efficient miners still online. But crunching the numbers, 1.88 million machines each pulling in 2.88 kWh over one entire year results in… ~47.6 billion kWh annually.

Another Bitmain machine purchasable today is the new T17 that generates 40 TH/s, drawing about 2200 watts at the wall. It would take about 2.5 million of these to generate the Bitcoin hashrate all while consuming… ~48.2 billion kWh per year.

To be thorough, Bitmain released the S9 SE in July which generates 16 TH/s, drawing 1280 watts. It’s unclear how many of these have been sold but if the entire network was comprised of these: 6.25 million would need to be used. And they would collectively guzzle ~70 billion kWh. This would be a plausible upper bound.

For comparison, if Bitcoin (T17) were its own country it would at minimum consume roughly the same amount of electricity as Romania or Algeria. If the network were comprised of just S9 SE’s, that’d be about the energy footprint of Austria. In either case, very little is value is produced in return… aside from memes and lots of social media posts. And no, despite historical revisionism by maximalists, “hodling” is not what Bitcoin was originally designed for.

As mentioned in the previous post: no other payment system on earth uses the same amount of electricity, let alone aggregate number of machines, as a PoW coin network. That is a dubious distinction.

In looking at my previous post you will see a similar figure. In August 2018, using the (older) S9 machine (~13 TH/s) as a baseline, the Bitcoin network consumed about ~50.5 billion kWh / year.1 Some of these types of machines (like the S9 SE) are still on.

Thus whenever you hear a PoW promoter claim that:

- Bitcoin doesn’t use much electricity; or

- Bitcoin’s electricity usage will naturally decline over time; or

- Bitcoin is more efficient than traditional payment systems

You can rightly tell them all of those claims are empirically false. In fact, the only way for the resource demands of a PoW coin to decline is if there was a long decline in the coin price.

What do taxpayers – who underwrite the state-owned utility companies – get in return for subsidizing these energy guzzlers? New economic zones of growth and prosperity?

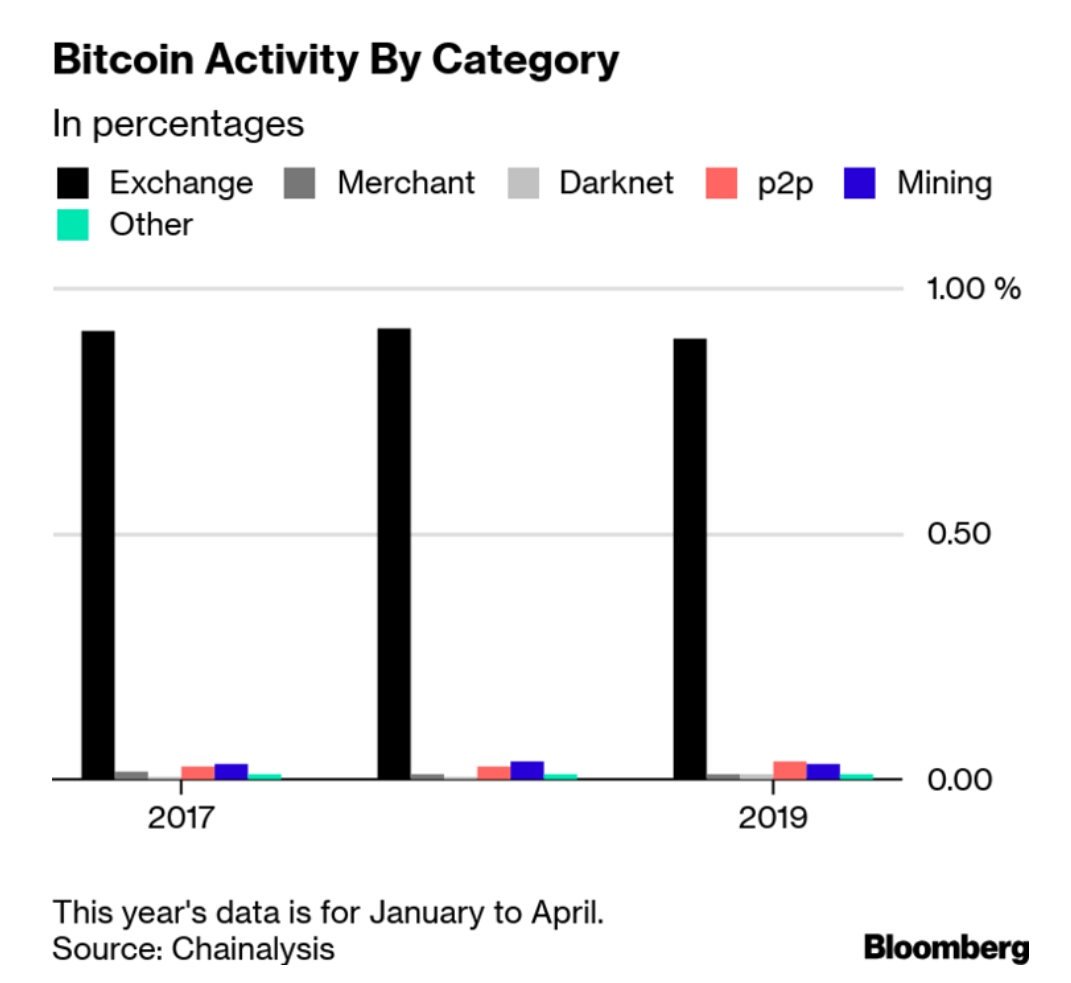

Nope. According to Chainalysis, in a given day more than 90% of activity on the Bitcoin network is simply movement from one intermediary to another. 2 Coin trading is by far the largest category.

And since most of these coin intermediaries increasingly require some form of KYC / AML compliance, the Bitcoin network has morphed into a expensive permissioned-on-permissionless network that has the drawbacks of both and the benefits of neither. There is no point in using PoW in a network in which all major participants are known: Sybils no longer exist.

A common refrain by PoW promoters is, Christmas lights and set-top boxes also consume huge amounts of energy!

First of all, that’s a whataboutism. But it also ignores how several Bitcoin mining manufacturers have actually tried to embed chips into these wares.

For instance:

- Bitmain has a couple of routers called the Antrouter that will mine either BTC or LTC for you.

- Bitfury has marketed Bitcoin mining light bulbs.

As you can imagine, a fixed unit of labor eventually becomes unprofitable once difficulty levels increase. It’s the same fundamental problem that faced the 21.co toasters. Thus neither of these took off (the light bulb didn’t ship) even though retail users often keep both their home routers and living room lights on all day. Historically PoW equipment becomes e-waste fast and the last thing consumers want is embedded e-waste that guzzles electricity.3

We haven’t even touched on other PoW coins such as Ethereum, Bitcoin Cash, or Monero… but it is worth pointing out that nearly all of the money going to miners via the block reward is value leaking from the system, either to semiconductor manufacturers or state-owned utilities.

This isn’t idle speculation either, as Nvidia counted on massive consumption of its GPUs in early 2018 which didn’t materialize due to the crash in coin prices. This led to a glut of high-end GPUs in its channel partners, which hit Nvidia’s bottom line and was later reflected by a 50% decline in share prices (the same phenomenon impacted AMD too):

Apart from a couple of small investments, the value that a couple of semiconductor manufacturers or a clique of state-owned utilities receives via mining is money that is not being invested towards developing the chain itself.

And some of these mining manufacturers have privatized gains at the expense of taxpayers. For instance, Bitfury, used its political connections to obtain cheap land in the Republic of Georgia where it setup massive mining farms:

“The efforts have given Georgia, with 3.7 million people, a dubious distinction. It is now an energy guzzler, with nearly 10 percent of its energy output gone into the currency endeavor.”

In Kyrgyzstan, 45 “crypto” mining firms consumed more energy than three local regions combined:

“[They] consumed 136 megawatts of electricity, which is more than the amount consumed by three Kyrgyzstan regions: Issyk-Kul, Talas and Naryn.”

Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Energy has introduced a new bill that would dramatically increase the electricity price to miners who are viewed as being “very energy intensive.”

We could probably create an entire post on these types of stories too.

At least Bitcoin is “decentralized,” right?

While the farms may be geographically dispersed to areas with the cheapest electricity, the mining pools, mining manufacturers, and other infrastructure participants are a small and centralized enough group that they can fit into a hotel for regular conferences.

Source: Twitter

Time to look at other chains.

Bitcoin Cash

Because it is nearly identical to Bitcoin (albeit with a few changes such as a larger block size), we can pretty much do the same set of calculations as we already did above.

Source: BitInfoCharts

Unlike Bitcoin, Bitcoin Cash has seen a dramatic decline in hashrate since it peaked at over 5 million TH/s earlier in the summer. It is now oscillating around 2.5 million TH/s.

For Bitcoin Cash, with a Bitmain S17e system, remember it generates 64TH/s and consumes ~2880 watts at the wall. If the entire network was comprised of the unreleased S17e-based machines, there would be around 40,000 of them. In a given year these would use about 985 million kWh. This will serve as our lower bound.

Bitmain’s S9 SE generates 16 TH/s, drawing 1280 watts. It’s unclear how many of these have been sold but if the entire network was comprised of these: ~156,000 would need to be used. And they would collectively use ~1.75 billion kWh. This would be a plausible upper bound.

Not counting e-waste, that would put the energy usage of Bitcoin Cash somewhere around 150, between Benin and The Bahamas. Compared with last year (when it was around 122), this decline is largely due to the nearly 60% price decline in BCH. This once again illustrates that hashrate follows price (e.g., miners expend capital chasing seigniorage).

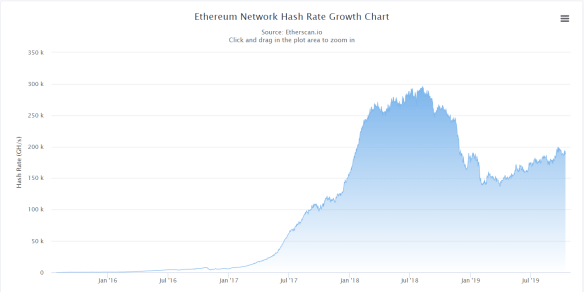

Ethereum

Coupled with “the thirdening” in February (in which block rewards declined from 3 to 2 ETH), and an overall decline in ETH prices, hashrate also declined over the past year:

Source: Etherscan

According to Coinwarz, the hashrate is oscillating around 200 TH/s, about 1/3 it was when the previous article was written.

A proposed ASIC from Linzhi that hasn’t been built or shipped aims to generate 1400 MH/s with an electricity consumption level of 1 kWh. As the story goes:

To put those figures in perspective, NVIDIA’s GTX TitanV 8 card is now one of the most profitable piece of equipment on the ethash algorithm, able to compute 656 MH/s at an energy consumption level of 2.1 kWh, according to mining pool f2pool’s miner profitability index.

There are a couple of other ASICs on the market including one from Innosilicon and another from Bitmain. The previous post looked at the same Innosilicon A10 on the market, so to simplify things and because the Bitmain machine is roughly just as efficient, let’s reuse it here.

The A10 generates 485 MH/s and consumes ~850 W. The Ethereum network is around 200,000,000 MH/s. That’s the equivalent of 412,371 A10 machines.

Annually these would consume about 3.1 billion kWh per year. Around 132, about as much as Senegal or Papua New Guinea.

If we used the GTX TitanV 8 card, as described in the article above, we find that 304,878 GPUs would be used. These would consume 5.6 billion kWh per year. That’d be around the same amount that Mongolia does annually.

This is one of the reasons why Ethereum is transitioning over to proof-of-stake. As Vitalik Buterin said last year:

I would personally feel very unhappy if my main contribution to the world was adding Cyprus’s worth of electricity consumption to global warming.

Will the nebulously defined “DeFi” on an actual proof-of-stake system change the usage dynamics in the future?4

Litecoin

Litecoin, better known as Bitcoin’s other testnet, has seen its hashrate decline along with its price.

Source: BitInfoCharts

For simplicity sake, let’s call it an even 300 TH/s which coincidentally it was at 14 months ago too. CoinWarz says it is also currently around that, who are we to argue with them?

As mentioned in the previous article, Bitmain’s L3+ is still around. It generates ~500 MH/s with ~800 watts. A slightly more powerful L3++ is on the market as well.

There are the equivalent of about 600,000 L3+ machines generating hashes.

As an aggregate:

- A single L3+ will consume 19.2 kWh per day

- 600,000 will consume 11.5 million kWh per day

- Annually: 4.2 billion kWh per year

It would be placed around 124th, between Moldova and Cambodia.

According a distributor, the Antminer L3++ specifications:

- Hash Rate: 580 MH/s ±5%

- Power Consumption: 942W + 10% (at the wall, with APW3 ,93% efficiency, 25C ambient temp)

If only L3++’s were used, the outcome would be about the same. 5

This consumption is pretty absurd once we factor in things like how there is only a couple of active developers who basically just merge changes from Bitcoin into Litecoin.6 In other words, one of the largest PoW networks has very few users or developers, yet consumes the same amount of energy as Moldolva. How is that a socially useful innovation?

Note: an easy way to double-check our math on this specific one: the price of LTC is nearly the same today as it was 14 months ago. Ceteris paribus, miners will expend capital no higher than the coin price, to ‘win’ the seigniorage.

Monero

In terms of mining, it appears that several decisions makers (administrators?) in the Monero world really dislike ASICs. So much so that they routinely coordinate forks that include “ASIC-resistant” hashing algorithms. Stories like this are mostly just PR because we know that any PoW coin with a high enough value, will eventually become the target of an ASIC design team.7

From the chart above, you can clearly see when the forks occurred that added “ASIC-resistance.”

Compared with the previous article, the hashrate has declined by about 1/3rd to about 325 MH/s. And it is believed that most of this hashrate is generated by GPUs and CPUs.

There are lots of how-to guides for building a Monero mining rig. Rather than getting into the weeds, based on this crazy 12-card Vega build, the user was able to generate 28,100 hashes/sec and consume 1920 watts. That’s about 2341 hashes per card (more than 10% faster than the one used in the previous article).

That’s about 138,829 GPUs each sipping 160 watts. Altogether these consume 194 million kWh annually. That’s likely a lower bound for GPU mining.

If we reused the Vega 64 mentioned in the previous article, there would be about 162,500 GPUs at the current hashrate. These would consume around 228 million kWh annually.

Not surprisingly, coupled with the “ASIC-resistant” fork and a coin price decline of nearly 50%, this resulted in about 1/3 energy used from the previous year. But this is still not an upper bound because it is likely that CPUs contribute to a non-insignificant portion of the hashrate via persistent botnets and cryptojacking.

Based on the same electricity consumption chart as the others, Monero would be placed somewhere above Grenada and the Mariana Islands. Perhaps a bit higher if lots of CPUs are used. Remember, this is called CPU-cycle theft for a reason.8

Conclusion

In aggregate, based on the numbers above, these five PoW coins likely consume between 56.7 billion kWh and 81.8 billion kWh annually. That’s somewhere around Switzerland on the low end to Finland or Pakistan near the upper end. It is likely much closer to the upper bound because the calculations above all assumed little energy loss ‘at the wall’ when in fact there is often 10% or more energy loss depending on the setup.

This is a little lower than last year, where we used a similar method and found that these PoW networks may consume as much resources as The Netherlands. Why the decline? All of it is due to the large decline in coin prices over the preceding time period. Again, miners will consume resources up to the value of a block reward wherein the marginal cost to mine equals the marginal value of the coin (MC=MV).9

This did not include other PoW coins such as Dash, Ethereum Classic, or Bitcoin SV… although it is likely that based on their current coin value they each probably consume less than either Litecoin or Bitcoin Cash.

Thus to answer the original question at the beginning, the answer is no.

PoW networks still consume massive amounts of electricity and semiconductors that could otherwise have been used in other endeavors. Some of these power plants could be shut down entirely. PoW-based cryptocurrencies crowd out and bid up the prices of semiconductor components.10 Apart from a few stories designed to pull on our heartstrings, little evidence exists (yet) for PoW coins creating socially useful economic output beyond moving coins from one intermediary to another.

And because most coins are mined via single-use ASICs, they generate large amounts of e-waste which leaks value from towards a small clique of semiconductor manufacturers and (mostly) state-owned utilities, neither of whom typically contribute back to the coin ecosystem.11 Will this change in the next 14 months?

Related links

- Bitcoin poses major electronic-waste problem (c&en)

- Cryptodamages: Monetary value estimates of the air pollution and human health impacts of cryptocurrency mining by Andrew L. Goodkind, Benjamin A. Jones, Robert P. Berrens

- Ethereum Plans to Cut Its Absurd Energy Consumption by 99 Percent (IEEE)

- Bitcoin doesn’t incentivize green energy by Max Feige (and the original)

- Verify, don’t trust (DigiEconomist)

- Will bitcoin’s price crash cut into its energy use? (The Economist)

- College campuses are the second-largest mining sector, research shows (The Block) privatized gains, socialized losses

- The doomsday economics of ‘proof-of-work’ in cryptocurrencies by Raphael Auer

- Miners shocked by electricity price surge in Washington State (The Block)

- Bitcoin ‘miners’ squander our electrical energy to feed warehouses packed with computers by Tom Karier

- Renewable Energy Will Not Solve Bitcoin’s Sustainability Problem by Alex de Vries

Endnotes

- I – and many others – have written about this before. PoW mining is a Red Queen’s race — miners are incentivized via block rewards to expend additional capital on mining, but the total reward available to miners is fixed. Thus while chip efficiency may increase each generation, miners as a whole increase capital outlays for equipment rather than reduce. [↩]

- According to The Token Analyst, nearly 7% of all mined bitcoins reside in exchanges. [↩]

- Another way some have used to describe Bitcoin is an ASIC-based proof-of-stake. But really it is DPOS but not with the “D” that you may be thinking. Since mining equipment rapidly depreciates (with a typical lifespan of less than 18 months), Bitcoin arguably uses depreciating proof-of-stake. [↩]

- According to both DappRadar and State of the Dapps, there has been about a marketed increase in “users” and Dapps (although they combine all Dapp platforms, not just Ethereum). [↩]

- Although obviously, as in all examples above, there are loses in efficiency as the energy travels from the power plant all the way through the grid and into a home or office. [↩]

- If there is only one actual developer maintaining the Litecoin codebase, how is this ‘sufficiently decentralized’ or not an administrator under FinCEN’s definition? Even the “official” foundation is basically out of funds. [↩]

- Wouldn’t it be interesting if a few botnet operators or sites like The Pirate Bay were moonlighting as Monero developers, so they could directly benefit from CPU mining? [↩]

- Outright theft continually takes place. For instance, a Singaporean allegedly stole $5 million worth of computing power to mine bitcoin and ether, and “for a brief period, was one of Amazon Web Services (AWS) largest consumers of data usage by volume.” [↩]

- See Bitcoins: Made in China and The Marginal Cost of Cryptocurrency by Robert Sams [↩]

- During the most recent bubble, DRAM prices soared in part because of demand from cryptocurrency mining. [↩]

- Emin Gün Sirer has done a good job explaining this ‘leakage.’ Recommend watching his Devcon 5 presentation on Athereum. [↩]