I recently finished reading the Kindle version of Number Go Up by Zeke Faux. This marks my 11th book review of cryptocurrency and blockchain-related books. See the full list here.

But… Number Go Up is marketed as a cryptocurrency book which is debatable. I would categorize it as True Crime with certain cryptocurrencies and centrally-issued pegged assets (like USDT) providing the enabling infrastructure.

It is a refreshingly witty book on a subject matter that is chronically filled with mindless conspiracy theories or Messianic price predictions.

Faux walked the tight rope, delivering a fairly nuanced and informative testament in an otherwise cacophonous market. Best of all it includes copious amounts of first-hand comments straight from the horses mouth of actual insiders, not wannabe social media influencers.

I read this back-to-back with Easy Money, by Ben McKenzie and Jacob Silverman, which was a dud in comparison. Easy Money was riddled with numerous mistakes that should have been caught when the manuscript was sent for independent fact-checking.

One quantitative example of how robust Number Go Up was, it contained 45 pages of references. In contrast, the shallow Easy Money contained a mere 8 pages of references.1 And while both books touch on some of the same topics (Tether, FTX, Celsius) and even interview some the same exact participants (SBF, Mashinsky, Pierce), Faux’s version of the events is not only richer in detail but often includes additional supporting characters… all without having to rely on an entourage.

Did I mention this was a witty book? In the margins I wrote: jhc, haha, lol, jesus, wow, burn and several variations therein about 25 times. It didn’t make the reader just laugh either. There were several times you could easily become angry, such as the face-to-face encounters that Faux had in Cambodia investigating romance-scam “pig butchering” compounds.

While the book occasionally discusses some technical concepts, it does not attempt to bog the reader down in a sundry of technical details. And when Faux did present something technical – like how a wallet works – he was in and out with the lesson in a few sentences.

If you could only read one book on the rise and fall of the most recent (virtual) coin bubble, be sure to check out Number Go Up.

With that said, despite the excellent prose and editing, I did find a few things to quibble about. But unlike the last two book reviews, there are no major show stoppers requiring a second edition to fix.

Prologue

Faux gets down to business, on p. 9 writing:

I’d like to tell you that I was the person who exposed it all, the heroic investigator who saw through one of history’s greatest frauds. But I got tricked like everyone else.

I’m not quite sure when I began following him on Twitter, but it has been at least a year. And not once during the collapse of the lending and exchange intermediaries last year did I see him do victory laps. Perhaps he did some quiet grave stomping late at night or on the weekend that I missed, but the tone of this book feels congruent with his online voice. And unlike the always-on coinerati (and anti-coiners who shadow them), the author upfront notes that he got tricked, we all did. 2

On p. 12 the author writes:

Thit is the story of the greatest financial mania the world has ever seen. It started as an investigation of a coin called Tether that served as a kind of bank for the industry.

As I pedantically questioned in other book reviews: by what measure was the 2020-2022 bubble the greatest financial mania the world has ever seen? Maybe it is, but in my adulthood the GFC seemed like at least a magnitude larger due to the existential issues of SIFIs and TBTF banks.

On p. 13 the author writes:

I pitched this book to my publisher in November 2021, near the mania’s peak, on the premise that crypto would soon collapse, and I’d chronicle the catastrophic fallout. Three months later, I was sitting with Bankman-Fried at his Bahamas office and looking at the computer screens behind his fuzzy head.

I think the author short changes himself a little here because chronologically he was already doing some sleuthing at the beginning of the year, attending Bitcoin Miami and other events.3 The timing is happenstance because not too far from his dayjob, according to Easy Money, both McKenzie and Silverman also met in a bar in New York to discuss pitching a book to a publisher at around the same time.

On p. 13 the author writes:

I told him my theory: that the coin called Tether, the supposedly safe crypto-bank that served as the backbone for a whole lot of other cryptocurrencies, could prove to be fraudulent, and how that could bring down the whole industry.

As mentioned above, I read this book immediately after completing Easy Money and in reading this particular sentence I had a small sense of déjà vu because that was their thesis too.4

Chapter 1: “I Am Freaking Nostradamus!”

On p. 15 he writes:

Don’t worry about how exactly a dog joke turns into a financial asset—even Dogecoin’s creator didn’t understand how it happened.

While Faux does provide a reference to an interview with Jackson Palmer, it bears mentioning to the readers that Dogecoin was co-created by two people, Palmer and Billy Markus.

On p. 16 he writes:

Jay wouldn’t admit he’d gotten lucky. He acted like his Dogecoin score proved his astute understanding of crowd psychology. Even after he moved on, I didn’t. I started seeing crypto bros everywhere. They were acting like the rising prices of the coins proved they were geniuses. And their numbers were growing.

This is an excellent observation. And when you attempt to engage some of them on social media more than a few will retort, HFSP!

On p. 17 he wrote:

Crypto didn’t hold the same appeal for me. I’d resisted the topic whenever it came up at work. It seemed so obvious. The coins were transparently useless, and people were buying them anyway. A journalist composing a painstaking exposé of a crypto scam seemed like a restaurant critic writing a takedown of Taco Bell.

This is one of the many witty comments, I’ll try not to post all of them because you should grab a copy of the book and find them yourself.5

On p. 18 he writes:

The answer was not much. But I did know they were called “stablecoins” because, unlike coins with prices intended to go up, they were supposed to have a fixed value of one dollar. That was because each coin was supposed to be backed by one U.S. dollar. The biggest stablecoin by far was called Tether.

This is a decent high level description of a centrally-issued pegged coin. In academic literature it is still probably more common to see “fixed” than “pegged” but either works.

With that said, I do think it is confusing – as a reader – to be introduced to Tether and not USDT. Later on it does get confusing, because the author uses Tether to describe both the issuer (Tether LTD) and the medium-of-exchange (USDT). I had a similar nitpick about the same type of usage in Easy Money, where the authors inexplicably do not fully define what a stablecoin is or mention how there is more than one (beyond Terra).

On p. 18 he writes:

I couldn’t tell which country’s authorities were overseeing Tether. On a podcast, a company representative said it was registered with the British Virgin Islands Financial Investigation Agency. But the agency’s director, Errol George, told me that it didn’t oversee Tether. “We don’t and never have,” he said.

One of the strengths of this book is that the author routinely gets a direct quote from people involved on the regulatory and law enforcement side of the table. Strangely we do not see anything like that in Easy Money.

On p. 19 he writes:

There were plenty of critics who speculated that Tether was not actually backed by anything at all.

Another refreshing sub-narrative in this book was the lack of a sub-narrative surrounding “critics” that occurred throughout Easy Money. That is to say, Faux does not attempt to put anyone on a pedestal, least of all, people marketing themselves as “critic” or “skeptic.”

On p. 20 he writes:

“In a panic, everything collapses and they look to the federal government to bail them out,” one attendee at Yellen’s meeting told me. “If the crypto market was isolated, maybe we could live with that. But hiccups in one market start to translate into other markets. These are the things we’re paid to worry about.”

The author referenced a series of important regulatory meetings that occurred in the summer of 2021 and actually got a direct quote from an attendee. Top notch stuff, no guessing games or reliance on clout chasers on Twitter.

Chapter 2: Number Go Up Technology

Great intro to the chapter on p. 22:

The Florida crime novelist Carl Hiaasen once wrote of his home state, “Every scheming shitwad in America turned up here sooner or later, such were the opportunities for predation.” In his books, the scheming shitwads are crooked cops, corrupt politicians, and the cocaine traffickers who financed much of Miami’s skyline. But plenty of people at Bitcoin 2021, the crypto conference I’d come to attend, met the description.

On p. 22 he writes:

I was deeply skeptical about cryptocurrency before I arrived, and what I had been learning about Tether wasn’t doing much to dispel those doubts.

Unlike the previous two book reviewed, the author does not make or spin this “skepticism” into some form of identity.

On p. 22 he writes:

My plan was to listen politely to a bunch of tech bros pitching their apps, and then to ask them what they knew about Tether.

And he did!

On p. 22 he writes:

The attendees wore T-shirts with crypto slogans, like Have fun staying poor or HODL, a meme about never selling crypto derived from a typo for the word “hold.”

He got it right! Unlike the previous two books reviewed, Faux discovered “HODL” was a typo from a drunkard.

On p. 24 he writes:

The mayor equated Bitcoin’s doubters with his city’s skeptics, who liked to needle him about climate change by pointing out that streets flooded even on sunny days. As it so happened, during the week of the conference, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had released a report calling for a massive, twenty-foot-high seawall across Biscayne Bay, blocking the ocean views of the city’s financial district. “You guys see any water here? I don’t know, I don’t see any water here,” Suarez joked to the crowd.

Can’t say I follow Suarez closely but does he typically use dark humor?

On p. 24 he writes:

Their bête noire was “fiat money.” That means money printed by central banks—in other words, pretty much all money in modern times.

I need to be pedantic (since that’s my calling card). In the U.S., the vast majority of “fiat money” is actually created by commercial banks not central banks.6

On p. 25 he writes:

A blockchain is a database. Think of a spreadsheet with two columns: In Column A there’s a list of people, and in Column B there’s a number representing how much money they have.

Hurray, a definition. Now I didn’t care much for the example the author used but unlike the previous book review, he gave it the good ol’ college try and it conveyed the necessary information to the reader.

On p. 25 he writes:

With the Bitcoin blockchain, the numbers in Column B represent Bitcoins.

Hurray, countable blockchains. Unlike several other books I have reviewed in the past (especially in the 2016-2017 era), Faux quickly explains to readers that there is more than one blockchain. Two sentences later he mentions the Dogecoin blockchain.

In other words, unlike Easy Money and Popping the Crypto Bubble, Faux does not conflate Bitcoin with every other blockchain.

On p. 26 he writes:

The technical innovation of blockchain is that it lets customers get together and maintain the list themselves, with no banker involved. If I want to transfer 1,000 Bitcoins from my account to someone else’s, there’s no handsy banker to call. So instead, my computer broadcasts the transaction to all the computers that run the Bitcoin network, sending all the other Bitcoin people a message that says, “Hey, I’m transferring 1,000 Bitcoins to another account.”

This is a decent example. But I think a more accurate verbiage would be “intermediary” instead of “bank” (because there are a variety of intermediaries in finance).7

On p. 27 he writes:

The solution that Bitcoin uses to prevent this “double-spending problem” is called “mining,” and it’s incredibly complicated and confusing. It also uses so much electricity that the White House has warned it might prevent the United States from slowing climate change. It’s like something out of the world’s most boring dystopian science-fiction movie.

This page is about as much as readers are provided into the topic of mining. That’s a little disappointing, since the market still lacks a long-form, non-hagiography on the topic. But that’s someone else’s calling for now and would not have really fit well into the flow of the book.8

On p. 28 he writes:

The difficulty of the game automatically increases when more miners enter it.

Technically the difficulty changes (increase or decrease) is based on hashrate, not on entry or exit of “miners.” That is to say, if readers were to download and use a Bitcoin mining client on their home computer, their mere entry would not immediately change the difficulty rating because the amount of hashrate a home CPU brings to bear is miniscule relative to the ASICs housed in warehouses by existing participants.

On p. 29 he writes:

Silk Road was Bitcoin’s first commercial application. Drug consumers didn’t set up their own mining rigs before going shopping on the dark web. They bought Bitcoins for cash on rudimentary exchanges. The demand started driving up the price.

To his credit, unlike Easy Money, Faux does not sensationalize and claim Silk Road was the “most successful onboarding app” for Bitcoin. Maybe it was, but Faux doesn’t get bogged down in histrionics.

On p. 30 he writes:

The system depends on economic incentives. The miners who confirm transactions have made such a large financial investment—in buying computers to compete in the guessing game—that it wouldn’t make economic sense to undermine Bitcoin by entering false transactions. But that also means it does make economic sense to run tons of computers to guess random numbers in hopes of winning the Bitcoin reward. As one person famously put it on Twitter, “Imagine if keeping your car idling 24/7 produced solved Sudokus you could trade for heroin.”

Solid quote. Nice reference to this funny tweet too:

On p. 30 he writes:

That is as bad for the environment as it sounds. Once Bitcoin’s price started rising, competition drove out the hobbyist miners. Within a few years, companies were selling specialized computers that were extra good at the guessing game. Miners started operating whole racks of them. Then warehouses full of racks.

This is a pretty concise way of describing the absurdity of the value leaking from the ecosystem, to the benefit of state-owned energy grids, A/C manufacturers, and semiconductor companies.9

On p. 31 he writes:

Other coins would adopt different authentication systems that used far less electricity, but Bitcoiners opposed any change to Nakamoto’s mining system. There was no way to reduce mining’s energy use.

This is a fantastic nuance that other authors, especially in both Easy Money and Popping the Crypto Bubble, fail to distinguish. The ossification and intransigence by the Taliban wing of Bitcoinland is real. For instance, the core developers (and foundations) behind both Zcash and Dogecoin have announced plans to migrate away from proof-of-work and adopt proof-of-stake.

While there have been (dubious?) efforts such as “Change the code” to kickstart something similar for Bitcoin, the bottom line is that it is the centralized exchanges that ultimately call the shots because they control the BTC ticker symbol. And during the blocksize “civil war,” several major ones said they would only recognize the chain that Bitcoin Core worked on. And that clique is anti-proof-of-stake. There will be a test after this book review, so take notes and pay attention!

On p. 31 he writes:

The fundamental absurdity of all this is that the numbers in the Bitcoin blockchain don’t represent dollars, or even have any inherent tie to the financial system at all. There’s no reason why a Bitcoin should be worth more than a Dogecoin or any other number in any other database. Why would someone burn massive amounts of coal just to get a higher number written in the blockchain for their account?

Preach it, brother! As Barney Gumble might say, just hook it to my veins.

On p. 31 he writes:

But, of course, just because the supply of something is limited doesn’t make it valuable—only 21 million VHS tapes of Pixar’s Toy Story were made at first, and you can get an original on eBay for three dollars.

Bingo! Without persistent and/or increased demand, a deterministic supply is mostly meaningless.10 Empirically we see that with hundreds (thousands?) of supply capped coins that fail to reach the proverbial NGU moon.

On p. 31 he writes:

For Bitcoin believers, the rising price became its own justification. On stage in Miami, many of the speakers resorted to a sort of illogical reasoning: The price of Bitcoin will go up because it has gone up. They wielded this circular argument to ward off doubt and call forth a future of infinite bounty. It became a mantra: Number go up.

To be fair, this mantra pre-dates the soothsayers at Bitcoin Miami by years. In fact, one could argue that the origins of Bitcoin maximalism – circa March 2014 – incorporated this fallacious circular view.

On p. 32 he writes:

“NUMBER GO UP,” declared Dan Held, an executive at a crypto exchange called Kraken, on stage at Bitcoin 2021. “Number go up technology is a very powerful piece of technology. It’s the price. As the price goes higher, more people become aware of it, and buy it in anticipation of the price continuing to climb.”

A sociologist or two could write a book on Held and his former colleague, Pierre Rochard, for the crazy things they have said to defend (and promote) Bitcoin maximalism.11

On p. 32 he writes:

Max Keiser, a Bitcoin podcaster, emerged first, in a white suit and purple sunglasses, to pounding EDM. “Yeah! Yeah!” he screamed, pumping his fists, as the dance music built to a drop. Elon Musk had recently said that Tesla would not accept Bitcoin due to its environmental impact, and Keiser was raging like the billionaire had run over his dog. “We’re not selling! We’re not selling! Fuck Elon! Fuck Elon!”

During my review of Chapter 6 of Easy Money, I linked to this exact string of expletives as something the authors missed by attending the 2022 edition of Bitcoin Miami and not the 2021 that Faux witnessed.

On p. 33 he writes:

A more accurate description would be that Saylor was the biggest loser in the room. He didn’t mention it during his talk, but his software company, MicroStrategy, had nearly gone bust during the dot-com bubble, back when the internet counted as a hot new technology. In 2000, just before it popped, he told The New Yorker: “I just hope I don’t get up one day and have to look at myself in the mirror and say, ‘You had $15 billion and you blew it all. There’s the guy who flushed $15 billion down the toilet.’ ” Right afterward, he lost $13.5 billion.

Solid quote. Strangely, while Saylor does get another couple of paragraphs, Faux missed out on informing the readers that on August 31, 2022, the Attorney General for DC announced it was suing Saylor for evading more than $25 million in taxes. Surely readers would find that interesting?12

On p. 34 he writes:

Some people speculated that what Tether called “commercial paper” was really debt from exchanges like FTX. That would explain why no one on Wall Street had dealings with Tether. FTX could simply send Tether a note saying, “I promise I’ll pay you $1 billion,” and Tether could zap over 1 billion coins, and no one would be the wiser.

Of all the discussion surrounding Tether, the commercial paper (CP) angle was the one that felt like it lacked a sufficient bowtie for readers. Later he does mention how Tether announced it planned to move entirely away from CP and acquire Treasuries instead.

However I felt that – as mentioned in the reviews of both Easy Money and Popping the Crypto Bubble – it would be helpful to the audience to briefly explain the recent history of shadow payments and shadow banking in the U.S., starting with PayPal and Money Market Funds (MMFs) which trail blazed the path that Tether LTD and other centralized pegged coin issuers followed.13

On p. 35 he writes about SBF and Tether:

“We’ve wired them a lot of dollars,” he said. He also told me that he’d successfully cashed in Tethers, transferring the digital coins back to the company and receiving real U.S. dollars in exchange, though the process he described sounded a bit strange. “This is going through three different jurisdictions, through intermediary banks,” he said. “If you know the right banks to be at, you can avoid some of these intermediaries.”

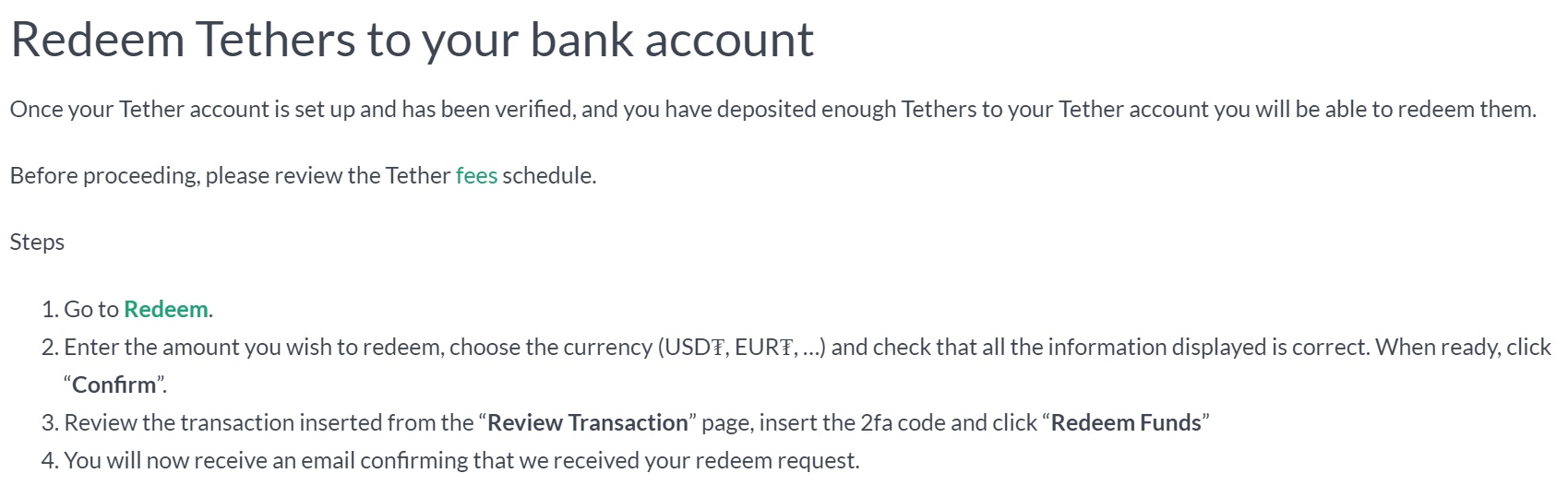

The long and the short of redeeming these centrally issued pegged coins is you have to rely on legacy infrastructure (wiring). I have never attempted to redeem USDT or USDC, but a number of acquaintances have, and following the collapse of SEN and SigNet it involves ol’ fashioned wires.14

On p. 36 he writes about Mashinsky and Celsisus:

But then he described what sounded very much like monkey business. Tether, in addition to investing in Celsius, had lent more than $1 billion worth of its coins to the company, which Mashinsky used to invest in other things. Mashinsky claimed this was safe because for every $1.00 worth of Tethers he borrowed, he put up about $1.50 worth of Bitcoin as collateral. If Celsius went bust, Tether could seize the Bitcoins and sell them. He told me this was a service Tether offered to other companies too.

So I don’t want to be perceived as carrying water for Tether (or Celsius) – I stand by all my critical comments I have made of both of them in the past – but this type of arrangement is kind of what commercial banks do. And that’s probably the angle – shadow banking – I would have probed more.

On p. 37 he writes:

“Somebody is lying,” Mashinsky said. “Either the bank is lying or Celsius is lying.” I was pretty sure I knew who was lying, and it wasn’t J.P. Morgan. I made a mental note to investigate Celsius when I got back to New York.

Why not both?

As mentioned in my review of Easy Money, in 2015, J.P. Morgan paid a combined $307 million fine to settle cases with the SEC and CFTC, admitting wrongdoing in part because certain banking units failed to tell clients it favored in-house funds, clear conflicts of interest. In 2020, J.P. Morgan paid $920 million to settle DOJ, SEC and CFTC charges of illegal market manipulation or “spoofing” in the precious metals and Treasury markets.

If the author was looking for a large unblemished regulated financial institution, there probably is none. But to be fair, this was Mashinsky’s example the author was responding to.

On p. 37 he writes:

Mallers explained that he had gone to a beach town in El Salvador because a surfer from San Diego was teaching poor people there about Bitcoin, which was somehow going to help them stop being poor.

Ha, this is great. And sad too.

On p. 37 he writes:

Rather than telling his citizens first, he had chosen to reveal a major national policy to a bunch of Bitcoiners, in Miami, Florida, in English, a language most Salvadorans don’t speak.

Oof.

On p. 38 he writes:

I didn’t get it. There was a reason no one used Bitcoin to buy coffee—it was complicated, expensive, and slow to use. And what would happen if poor Salvadorans put their savings in crypto and then the price fell? But the audience was rapt. As I scanned the crowd, I saw that Mallers wasn’t the only one wiping away tears.

If there is a movie version of this book, need to have Steve Martin-like entertainer on stage ala Leap of Faith.

On p. 39 he writes:

Not everyone I spoke to in Miami was a Bitcoin cultist. The biggest users of Tether were professional traders at hedge funds and other large firms, and I interviewed several of them too. What they explained to me was that for all the talk of peer-to-peer currency, and the ingenuity of a way to transfer value without an intermediary, most people weren’t using cryptocurrencies to buy stuff. Instead, they were sending regular money to exchanges, where they could then bet on coin prices.

Compared to the two previous books, it is nice to see the author use a nuance around “Bitcoin cultist” — because not every coin or token encourages the sort of maximalism we see from Dan Held and Pierre Rochard. And empirically not every public chain project is attempting to reinvent “money.”

On p. 39 he writes:

Even so, many had their own conspiracy theories about Tether. It’s controlled by the Chinese mafia; the CIA uses it to move money; the government has allowed it to get huge so it can track the criminals who use it. It wasn’t that they trusted Tether, I realized. It was that they needed Tether to trade and they were making a lot of money doing it. There was no profit in being skeptical. “It could be way shakier, and I wouldn’t care,” said Dan Matuszewski, co-founder of CMS Holdings, a cryptocurrency investment firm.

I’m not endorsing CMS but I’ve found it weird to see certain Tether Truthers single out CMS as part of the inner ring of the Tether cabal.15 One of its most vocal members even accused Matuszewski of lying about redeeming USDT for real money, and then deleted the tweet. Maybe CMS (and Matuszewski) are indeed at the center of the Tether cabal, but the burden-of-proof is on the Truthers (the self-deputized prosecutors) to provide evidence.

Chapter 3: Doula for Creation

One of the most interesting things about this chapter is the author described, what I believe may have been the first bookform exploration into the history of Mastercoin.

I’ve read a number of interviews of Brock Pierce in the past. I even briefly met him in late 2014 at a house party in the Bay area. But this was the most colorful description of his social circle, drugs, dreams and all.

For instance, on p. 42 he writes:

I decided to mingle and ask the guests what they knew about our absent host. A beautiful woman told me she’d spent a week with Pierce in the Colombian jungle, where he’d bought land to protect it for Indigenous people. “It’s amazing what he does,” she said. Another man told me Pierce was building a spaceport on an old army base in Puerto Rico. An obnoxious guy who described himself as a “futurist” told me a story about a time in Ibiza when Pierce went three days without sleeping. “He’s surrounded by people who are benevolent dolphins and not sharks,” he said. He then asked me to smell a pastry for him before he ate it, telling me he was allergic to raspberries.

Ha! Everything in this paragraph is worth a couple chuckles because anecdotally it sounds true.

On p. 43 he writes:

A doctor from Boise, Idaho, and a Bitcoiner were talking about the coronavirus vaccine and “medical freedom.” The Bitcoiner refused to tell me his name. “Real G’s move in silence,” he told me, with a high-pitched laugh.

Sounds par for the course. I’ve lost count how many supposed “cypherpunks” want to have it both ways: cash in off their notoriety and live it up large all while being “anonymous.” Jameson Lopp immediately comes to mind: telling The New York Times how he made himself “vanish” and simultaneously getting CryptoDeleted, deleted.16

On p. 44 he writes:

None of the guests seemed to know one another. A crypto venture capital fund manager—wearing a mock souvenir T-shirt from convicted pedophile Jeffrey Epstein’s private island—joked about a scam that another yacht guest was running. A crypto public relations man offered what he called “Colombian marching powder” to a young woman.

So much oof in those three sentences.

On p. 46 he writes:

I realized I had walked in on a presentation for a timeshare that I would pay money not to join. It was also not the best setting for a long conversation. My tour guide soon sent me back downstairs. When Pierce and I did catch up, by phone, he told me he’d dreamed up the idea for a stablecoin back in 2013. He said he knew from the start it would change the course of history. “I’m not an amateur entrepreneur throwing darts in the dark,” he told me. “I’m a doula for creation. I only take on missions impossible.”

Someone should call the police, the author was subjugated to some cruel and unusual punishment.

On p. 49 he writes:

By 2013, Pierce was running one of the first Bitcoin venture capital funds. There still wasn’t much you could do with Bitcoins, and crypto remained largely the domain of geeks and hobbyists. But around that time, a man going by “dacoinminster” had posted a proposal on the popular message board Bitcointalk that would lead to the creation of Tether and make the entire $3 trillion cryptocurrency bubble possible. He called his idea “MasterCoin.”

I think one detail that could have been worth adding was that this fund was originally called Crypto Currency Partners and during the “bear market” of 2015 rebranded to Blockchain Capital. The fund typically wrote small checks (around $25,000 per deal) and had spurned at least one VC rule at that time: do not invest in startups that competed with one another (e.g., if you invest in one exchange in a specific jurisdiction, then do not invest in another exchange that served the same jurisdiction).

On p. 50 he writes:

Willett imagined that once he created the MasterCoin system, other people would come up with all sorts of ways to use it: coins that tracked property titles, shares of stock, financial derivatives, and even real money. None of the ideas were completely original—he told me he’d read many discussions of them on message boards—but he was the first to put them into practice.

Could be worth mentioning that there were several (three?) colored coin projects that existed around the same time, attempting to track similar off-chain wares.

On p. 50 he writes:

“If you think Bitcoin has a reputation problem for money laundering now, just wait until you can store ‘USDCoins’ in the block chain!” Willett wrote in 2012. “I think criminals (like the rest of us) will prefer to deal with stable currencies rather than unstable ones.”

Pretty prophetic. Although, unclear from his original post if Willett was thinking of any distinction between central bank-issued digital currency versus privately issued pegged coins (which is what we have ended up with so far).

On p. 51 he writes:

Willett’s plan was innovative. It was also illegal. What Willett did was a textbook example of what the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission calls an “unregistered securities offering,” meaning that Willett was selling an investment opportunity without any of the usual safeguards. Willett told me that the agency probably would have fined him hundreds of thousands of dollars if it had noticed what he was up to. But luckily, the regulators weren’t reading Bitcoin message boards. “They would have made a terrible example out of me if they’d known what was coming,” Willett said, laughing. “Never heard anything from them.”

So both Willet and the author could be correct. But I think referencing or quoting a U.S.-licensed attorney would have made this a stronger paragraph.

On p. 51 he writes:

Phil Potter, an executive at an offshore Bitcoin exchange, Bitfinex, was developing a similar idea. They teamed up and adopted Potter’s name for it: Tether. (Potter told me he was actually the one to first approach Sellars with the idea. “I’m sure Brock will tell you he came down from Mount Sinai with it all written on stone tablets,” he said.)

This is one of those quotes I spit-the-coffee-out, so to speak. You see, in Easy Money, the authors never got a direct quote from anyone at Tether, Bitfinex, or the regulators who oversee them. It was a disappointment. In contrast, readers of Number Go Up get a chance to hear from all of the above.

On p. 52 he wirtes:

Tethers. Then Tethers could be transferred anonymously, like any other cryptocurrency.

Pedantically, it isn’t truly anonymous: it is pseudonymously.

On p. 52 he write:

The problem was that Tether, like other cryptocurrencies, broke just about every rule in banking. Banks keep track of everyone who has an account and where they send their money, allowing law enforcement agencies to track transactions by criminals. Tether would check the identity of people who bought coins directly from the company, but once the currency was out in the world, it could be transferred anonymously, just by sending a code. A drug lord could hold millions of Tethers in a digital wallet and send it to a terrorist without anyone knowing.

I partially agree with this but believe a clarification should be added: in the U.S. That is to say, not every country has the exact equivalent of the “Bank Secrecy Act” which is what the author is referring to here.17

Three years later I would probably amend my own tweet to state on-chain activity can be surveilled by anyone running a node (tracing can be done at any time). But that surveillance sharing from CEXs depends on jurisdiction.

On p. 52 he writes:

“The U.S. will come after Tether in due time,” Budovsky wrote me in an email from a Florida prison. “Almost feel sorry for them.”

This was another spit-the-coffee-out moments. Unlike the authors of Popping the Crypto Bubble and Easy Money, Faux reached out to the creator of Liberty Reserve for a quote. And got a relevant one. Solid reporting.18

On p. 54 he writes:

When I spoke with Pierce on the phone, I asked him the central question: Was Tether actually backed up by real money? He assured me it was. He said Tether was preserving the dollar’s status as a global reserve currency. “If it were not for Tether, America would likely fall,” he said. “Tether in many ways is the hope of America.” But as he droned on, I realized Pierce had little information to offer about the location of Tether’s funds. My mind started to wander.

To me, this was the correct way to frame the conversation for the reader: Pierce is not an insider, so he probably does not have up-to-date inside info. I pointed this out in the review of Easy Money, where McKenzie and Silverman felt compelled to include Pierce’s information-free banter.

On p. 55 he writes:

But Pierce wasn’t going to help me find salvation. He told me that he’d actually given up on Tether in 2015, about a year after he started it. The currency had gotten almost no users, and it seemed likely it would be frowned upon by authorities. An SEC lawsuit, or a trip to prison, would prevent him from reaching his own destiny. “My view was if I made money from this thing it would prevent me from doing the work that I have to do for this nation,” Pierce said.

Unclear if Pierce truly believes the tales he spins.

On p. 55 he writes:

But if the exchange used Tethers instead of dollars, it wouldn’t need them. Potter pitched this idea to his boss at the exchange: Giancarlo Devasini, the Italian former plastic surgeon. He went for it. Devasini and his partners already owned 40 percent of Tether, and they bought the rest from Pierce’s crew for a few hundred thousand dollars. Pierce told me he handed over his shares for free.

This passage is another example for why I think Faux probably should have used Tether LTD to describe the issuer and USDT to describe tethers. A casual reader might assume that Devasini owns 40% of the USDT supply.

On p. 55 he writes:

After interviewing most of the people involved with Tether’s creation, I realized that they didn’t have the answers I was looking for. All of them said something similar: They definitely deserved credit for coming up with one of the most successful companies in the history of cryptocurrency, but they bore no responsibility for whatever the company was doing now.

Ha!

Chapter 4: The Plastic Surgeon

This is one of the shortest chapters, but involves some interesting color on Giancarlo Devasini that has not appeared in print before.

For instance, on p. 59 he writes:

This didn’t exactly match what I’d read on Bitfinex’s website. There, it said that Devasini’s group of companies brought in more than 100 million euros a year in revenue, and that he sold them shortly before the 2008 financial crisis. But Italian corporate records showed that the companies had revenue of just 12 million euros in 2007. Some of them even filed for bankruptcy. And none of the former employees I spoke to remembered Devasini selling them.

An example of “exit inflation”?

On p. 59 he writes:

What they did tell me was that in 2008, Devasini’s production facility was destroyed in a fire. Fuxa said it was caused by diesel generators that Devasini had set up because the local utility hadn’t provided enough power. “He basically built a power plant in the back and it went up in smoke,” Fuxa told me. But a newly unprofitable factory burning down in a mysterious fire struck me as a potential red flag, waving in the distance.

Oof.

On p. 60 he writes:

Tether called the lawsuit “meritless” and said it went nowhere.

Perhaps it is stonewalling, but a canned response is arguably better than simply not even reaching out to Tether LTD, which is apparently what a lot of the people who market themselves as “Tether Critics” have done. Solely engaging on Twitter has its limitations.

On p. 63 he worte:

Devasini was fascinated with finance. In a December 2011 post titled “The Shell Game,” he explained how Italian banks could avail themselves of billions of dollars of low-interest-rate funding. They could use it to gamble on anything, or to buy higher-yielding government bonds to make risk-free profits.

December 2011 was the middle of the European debt crisis (Italy was one of the i’s in PIIGS). Spoiler alert: since then, a number of Italian banks have struggled in what is labeled “the doom loop,” which includes the oldest Italian bank, Montei dei Paschi (which was bailed out). Would the banking sector be different if they had followed Devasini’s suggestion? Not sure, but is it a straight line between this “shell game” post and the setup of Tether LTD threeish years later?

Chapter 5: Hilariously Rich

On p. 66 he wrote:

He’d been left with a stockpile of 20 million unsold CDs and DVDs from his defunct manufacturing business. Now he decided to sell them for Bitcoin. He posted an ad on the Bitcointalk forum offering them for 0.01 Bitcoin each—about ten cents at the time. Marco Fuxa, his former business partner, told me that Devasini sold them all. If that’s true, and he kept the Bitcoins, their value would have later soared to more than $3 billion. “That’s how he got his money,” Fuxa said.

Big if true.

On p. 66 he wrote:

The first big exchange, Mt. Gox, repurposed a website created as a place to trade virtual Magic: The Gathering cards. (“Mt. Gox” stands for Magic: The Gathering Online eXchange.) Unsurprisingly, a former trading card website proved to be a bad custodian for billions of dollars.

It is interesting to see what different authors decide to include and omit to provide readers a backdrop to the industry they are covering. The collapse of Mt. Gox in 2014 unilaterally led to a 2+ year bear market and is frequently highlighted in mainstream press including this book. Yet neither Easy Money nor Popping the Crypto Bubble mentioned it even though it might have helped their arguments.19

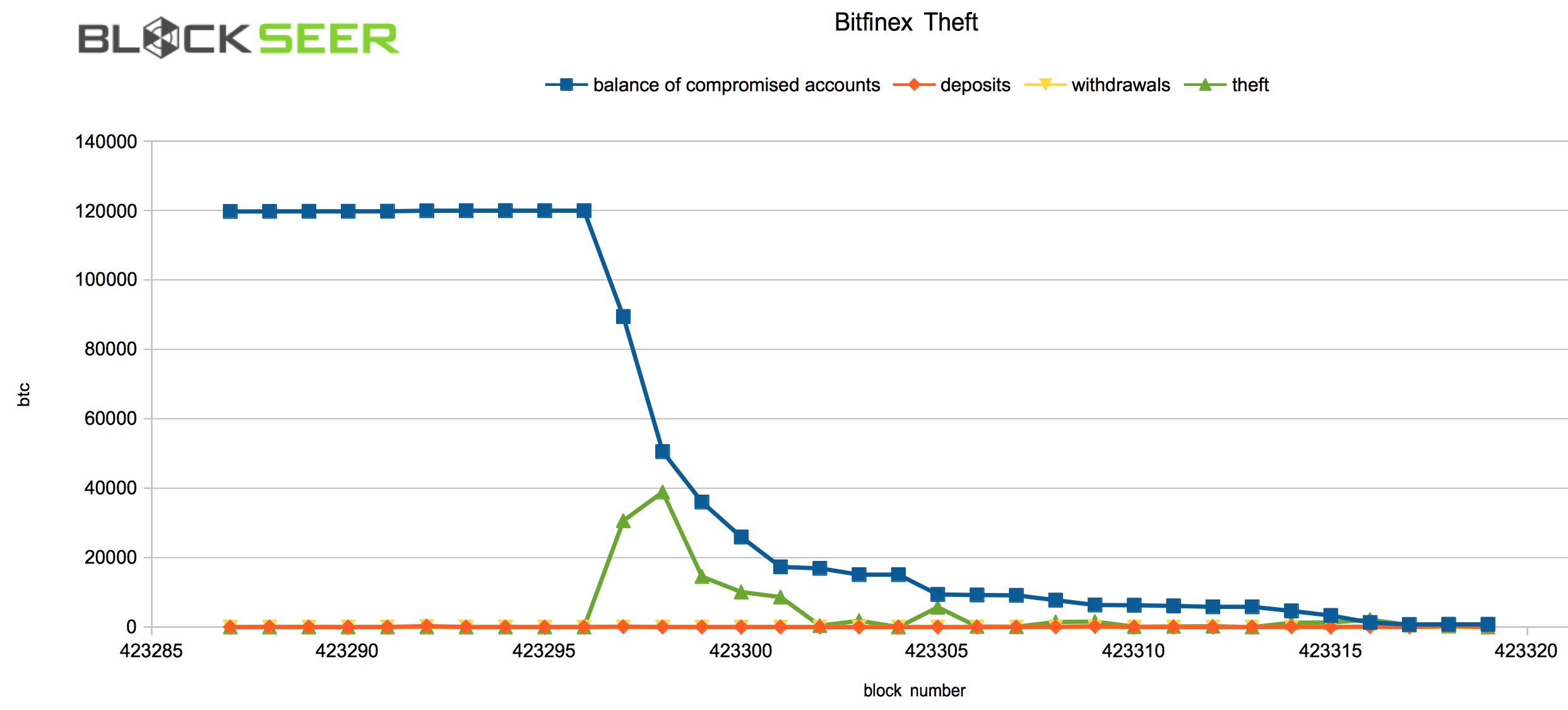

On p. 67 he wrote about the aftermath of the 2016 Bitfinex hack (the 2nd one):

Trading increased so much that within eight months the exchange had earned enough to pay back its customers, either in cash or in Bitfinex stock. With this gambit, Bitfinex earned customers’ loyalty. And judging from what he’d do in the next few years, Devasini had learned a lesson: He could get away with bending the rules.

Even though I am not a trader, this always rubbed me the wrong way. If a regulated financial intermediary (like a custody bank) had done something similar in 2016, it is hard to see how the scrip would have been permitted to be issued. But we’ve seen some pretty strange things in traditional finance too ¯_(ツ)_/¯.

On p. 68 he writes about ICOs:

The hype was so powerful, it seemed like anyone could post a white paper explaining their plans for a new coin and raise millions. Brock Pierce, the Tether co-founder, promoted a coin called EOS, which was pitched as “the first blockchain operating system designed to support commercial decentralized applications.” It raised $4 billion. Yes, really. “I don’t care about money,” Pierce said in an interview around that time. “If I need money, I just make a token.”

Perhaps stranger is that Block.one (the entity that conducted the ICO) settled with the SEC in 2019 for $24 million with no disgorgement. Does this mean that EOS is in the clear now (in the U.S.)?

On p. 68 he writes:

These ICO-funded start-ups promised that blockchain would revolutionize commerce by enabling provenance to be tracked and verified. Even big companies like IBM and Microsoft started saying that they would put practically everything on the blockchain: diamonds, heads of lettuce, shipping containers, personal identification, and even all the real estate in the world. It seemed like blockchain-powered ICOs were the practical use that crypto had been waiting for. But there was one problem. None of this stuff ever advanced beyond the testing phases, if anyone bothered to even do that. Most ICOs were scams. And they weren’t actually an innovative form of fraud. ICOs made it easier to run a scam that’s about as old as the stock market. It’s called a “pump-and-dump” scheme.

I think this needs a paragraph break after the first sentence. Because while accurate, some readers may think that companies like IBM or Microsoft were directly involved in ICOs at that time (they were not).20

On p. 69 he writes:

With help from Mayweather, Centra raised about $25 million. But like most of the companies that raised money with ICOs, it was a total scam. It never issued its crypto debit card, or anything else at all. Even the CEO listed on its website didn’t exist—his picture was a stock photo. It would later be revealed that its founders, including a pot-smoking, opioid-addled twenty-six-year-old who ran a Miami exotic car rental business, had paid Mayweather $100,000 for his endorsement.

In contrast to Easy Money, where one of the authors talks about smoking pot and eating edibles a few times, this is the only place that marijuana is mentioned.21 Is that a good or bad thing? As Buddy Holly might say, Faux’s writing is square.

On p. 72 he writes:

By early 2017, Bitfinex was keeping its money in several banks in Taiwan. But the way the international financial system works, running an exchange required the cooperation of other banks too. Bitfinex’s Taiwanese bankers relied on other banks—known as correspondents—who acted as middlemen to pass money from Taiwan to customers in other countries.

One of my former colleagues at R3 previously worked at a large bank in Taiwan. When this publicized debanking occurred he mentioned in speaking with his former colleagues, senior managers who finally learned what was happening viewed it as scandalous because Bitfinex was flagrantly bypassing risk controls by opening up new accounts under different names.22

On p. 73 he writes:

But somewhere in the United States, an I.T. worker in his early thirties spotted the filing for the abortive lawsuit after it hit the court docket. He couldn’t believe what he was reading. Tether was supposed to be backed by real U.S. dollars in a bank. But in the lawsuit, the company itself admitted it had no access to the banking system. What was especially odd was that even after filing the case, Tether kept issuing coins. It created 200 million new ones that summer. But was anyone even sending in the corresponding $200 million, if the company didn’t have a functional bank account? The man signed up for Twitter, Medium, and other social media platforms under the pseudonym “Bitfinex’ed.” And what he started posting would create big problems for Devasini. Tether had spawned a powerful troll.

I believe one of the first times I interacted with Bitfinex’ed (prior to him losing a bet and blocking me), was when he proof read my post discussing the court case above: How newer regtech could be used to help audit cryptocurrency organizations.23

In retrospect, maybe I should have trademarked one of the subtitles: “Tether is not so tethered.”

Chapter 6: Cat and Mouse Tricks

On p. 74 he writes:

Four years later, when I started looking into Tether on my Businessweek assignment, Bitfinex’ed was still posting multiple times a day. His writing was conspiratorial, but it had struck a chord. Everyone in crypto would bring his posts up in conversation with me. Tether defenders tended to blame him for any negative news about the company. I’d seen things he wrote echoed in lawsuits and in mainstream reports. He seemed to know so much about Tether that I wondered if he worked for the company, or if he was a disgruntled government investigator. I arranged a meeting with him, on the condition I wouldn’t reveal his identity.

As mentioned in the Easy Money review, the first search result for googling “Bitfinexed identity” is to a five year old article that links to a Steemit article. Bitfinex’eds name is Spencer Macdonald.24 Back when I wrote long newsletters Bitfinex’ed was on my private mailing list and sent me the link to a Steemit article of a guy who “doxxed” him because Macdonald had re-used the same catchphrases “Boom. Done.” under an alias Voogru on reddit.25

On p. 75 he writes:

He told me that he didn’t want to reveal his real identity because he’d gotten death threats from Tether defenders. As he worked himself up, the pitch of his voice rose higher.

That sucks, I have also received a slew of threats (and petty grievances) in the past too. The people who send those threats should receive some kind of consequence. Putting that aside, why does he still use this alias at this point since it has been googlable for years?

On p. 75 he writes:

By then, Andrew had lost me. I had been hoping to get new leads at this meeting, not an analogy drawn from a cartoon about anthropomorphic ducks. Andrew told me his mission to expose Bitfinex wasn’t personal. It seemed like it was. He said he imagined Kevin Smith—who played a slovenly hacker named Warlock who works out of his mother’s basement in a Die Hard sequel—portraying him in a movie. “I think it’s more humiliating for Bitfinex that way,” he said.

I agree with Faux, it seems a bit personal too. And I don’t think there is any shame in admitting that: several Bitfinex/Tether LTD staff (executives?) wronged you in the past — plus repeatedly lied in public — and you want to get even. But Macdonald – like the rest of the Tether Truther gang – likely has no inside information, he says as much to Faux. So how does Macdonald plan to humiliate them? In Easy Money, James Block dropped the alias (DirtyBubbleMedia) and still uses chain analytics to trace linkages, why not follow his lead?

On p. 77 he writes:

When I asked for his sources or evidence, Andrew didn’t have anything new to provide. That was where I was supposed to come in.

This is a big oof. In Easy Money the authors put Macdonald/Bitfinex’ed on a pedestal, but never present a smoking gun. Perhaps there is one, but that rabbit hole took up valuable page space that Faux instead uses to interview a prosecutor from the NY AG office.

Speaking of speculation, Matt Levine recently hypothesized that Tether could be a lucrative business for one of the following reasons:

Number 2 is a possibility that Faux also independently surmises in the book, yet the authors of Easy Money do not, possibly because their sources (Bitfinex’ed/Macdonald) dismiss it a priori.26

On p. 77 he writes:

Betts explained that Noble wasn’t exactly a bank—it was an “international finance entity,” organized under looser Puerto Rican laws. His plan was to open accounts for all the major cryptocurrency hedge funds and companies. That way, they could easily transfer money between themselves without ever sending it out of Noble.

The Drake meme seems pretty fitting for this passage:

On p. 78 he writes:

The dispute got so heated that Devasini wanted to pull the company’s cash from Noble. Devasini’s deputy, Phil Potter, wanted to keep their money in the “international finance entity,” so Devasini and his other partners bought him out for $300 million. Potter took the payment in U.S. dollars, not Tethers.

That is a pretty big chunk of change. From its neighboring paragraphs, it appears this buyout took place in 2018. How did the partners who bought him out fund that buyout during this time period?

Chapter 7: “A Thin Crust of Ice”

This was a great chapter if for no other reason than we get to read in booklength (for the first time?), from a NY AG prosecutor involved in the Tether case. After reading this book, I think going forward reporters should ask Tether Truthers if they have ever reached out and/or spoken to any of the prosecutors. That seems like the bare minimum low-effort task to complete, otherwise it is just LARPing as a social media maven.

On p. 80 he writes about John Castiglione and Brian Whitehurst who were assigned to investigate the cryptocurrency market for the NY AG.

On p. 81 he writes about subpoenas:

The crypto industry responded with outrage. Four exchanges didn’t respond at all. Some of the others said they had no responsibility to police suspicious activity. Castiglione and Whitehurst decided to focus on Bitfinex, the crypto exchange owned by the same group that owned Tether. It had the most red flags. The company said it didn’t do business in New York, but one of its top executives—the chief strategy officer, Phil Potter—lived there. Castiglione sent a subpoena to some New York trading firms, and they informed him that they did use Bitfinex.

One of the exchanges that said they would not respond was Kraken whose representatives, at the time, said they did not do business in New York. Yet curiously, a year later, their head of trading – who was based in New York – sued them for stiffed compensation.

On p. 82 he writes:

This was, amazingly, even sketchier than it sounds. Crypto Capital advertised on its website that it enabled users to “deposit and withdraw fiat funds instantly to any crypto exchange around the world.” But it didn’t have any special technology. Instead, it was essentially a money-laundering service. Crypto Capital would simply open bank accounts using made-up company names. They’d tell banks they’d use the accounts for normal things, like real-estate investing. Then they’d let companies like Bitfinex use them for customer transfers. (Bitfinex would later claim that it believed Crypto Capital’s assurances that everything was on the up-and-up.)

Amazing, plus a funny parenthetical.

On p. 83 he writes:

Castiglione and his colleagues asked for proof that all Tethers were paid for with actual dollars by real customers. The defense lawyers acted affronted. But after some back-and-forth, one of the defense lawyers acknowledged that there had been what he called a “development.” They didn’t exactly come clean. Bitfinex had placed more than $850 million with a payment processor—Crypto Capital—and it appeared to be “impaired,” he said. Bitfinex had filled the hole by borrowing from Tether’s reserves. “I’m sorry, can you say that again?” Castiglione asked. Castiglione couldn’t believe it. Impaired seemed to be a euphemism for “gone,” and gone meant the exchange was insolvent and on the brink of collapse. On Wall Street, a trading venue in this situation would have to tell the world and shut down. It seemed like Bitfinex didn’t even plan on informing its customers. Castiglione asked the defense lawyers to leave so he and his colleagues could confer in private.

Future writers and reporters: if your book on Tether doesn’t have something as juicy as this statement above, do more digging because this is the bar to surpass.

On p. 85 he writes:

At first, Bitfinex’s lawyers said the deal to lend themselves Tether’s money was only pending. But after weeks of exchanging letters, they informed Castiglione that it had been completed, though they assured him it was a fair transaction negotiated without conflict of interest. They sent over papers documenting a $900 million line of credit from Tether to Bitfinex. Signing on behalf of Tether was Giancarlo Devasini. And on behalf of Bitfinex: Giancarlo Devasini.

They got the last laugh though, right? In the process of writing this, Tether LTD announced its latest attestations: about 85% of their reserves were now supposedly held in cash and cash-like equivalents (Treasuries). If they are able to pocket the 5%+ yield on Treasuries that is at least a couple billion in annual profit.27

On p. 86 he writes:

The settlement with New York required Tether to publish quarterly reports detailing its holdings, and to send even more detailed information to the attorney general. Castiglione hoped they would inspire someone to look more closely. But no regulators asked to see them.

This is interesting. Why have no other regulators reached out to see the documents? Did other regulators and law enforcement receive similar documents from subpoenas and thought the NYAG had outdated material?

Chapter 8: The Name’s Chalopin. Jean Chalopin.

On p. 91 he writes:

Tether’s lawyer, Stuart Hoegner, had a little bit more to say to me. In a video chat, he called Tether’s critics “jihadists” set on the company’s destruction and said their market-manipulation claims didn’t make sense. And, in an email, he said my reporting was “nothing more than a compilation of innuendo and misinformation shared by disgruntled individuals with no involvement with or direct knowledge of the business’s operations.”

It is not clear when Hoegner had the change of heart, or maybe it is just in external communications? You can always fire your client to save your book credibility.28

On p. 93 he writes:

That October, Businessweek published my account of what I found, with the headline “The $69 Billion Crypto Mystery.” (By then, Tether had issued 69 billion coins.)

Portions of the ~5,000 page article was reused throughout the book. Perhaps because the photo is black & white Jean Chalopin kind of looks like Chuck Norris.

On p. 93 he writes:

People read into the story whatever they wanted to believe. To crypto fans, it showed that Tether did in fact have at least some money, which was a positive. To those who were skeptical, the information about Chinese commercial paper was damning. I wasn’t sure what to make of the financial records myself. I tried digging into the details of their holdings. Many of the loans appeared to be legitimate loans to real companies. Others I couldn’t verify at all. But that was unsurprising given the low quality of data on Chinese corporate loans. Rather than a smoking gun, the records felt like another inconclusive clue.

He hasn’t received a smoking gun so far. Other authors on the beat take note, it’s okay to say you don’t have conclusive evidence one way or the other.

On p. 94 he writes:

“I’m betting a shit-ton of money on them being a crook,” Fraser Perring, co-founder of Viceroy Research, told me. “Worst case is, I can’t lose hardly anything. I’m already rich, but I’m going to be fucking rich when Tether collapses.”

In Easy Money, the authors obliquely refer to a hedge fund (when interviewing James Block). I hypothesized it could have been Hindenburg Research or Citron (the former is mentioned later in this book). How many hedge have active trading positions on Tether solvency (one way or the other?)

On p. 95 he writes:

More recently, in March 2023, California’s Silicon Valley Bank collapsed after worry about its investment portfolio, amplified by a prominent podcaster, caused its customers, mostly start-up executives, to freak out.

Faux references a Financial Times article highlighting Jason Calcanis, who is a co-host of the All-In Podcast. Calcanis’ hysteria has led to a number of memes (and at least one bankrupt bank):

On p. 96 he writes:

But none of the analysts seemed much better informed than “Andrew,” the conspiracy theorist I’d met who posted as “Bitfinex’ed.”

Oof. Watch your notifications: FactFreeh, WillyBot, and other anonymous accounts will troll you if you point that out on the bird app.

On p. 97 he discusses the $1 million bounty from Hindenburg Research:

In November, we met in front of a hot dog cart by an entrance to Central Park. Anderson showed up wearing a hoodie. As we strolled down a path past children playing baseball, tourists taking photos, and a steel-drum band, he talked about what he could do with detailed documents on Tether’s holdings. Anderson said the bounty announcement hadn’t produced any great tips so far. I told him I might be able to help. Without revealing any details, I described the documents that I’d received.

I feel a little vindicated because in the past I have asked Tether Truthers, such as Jorge Stolfi, if they were so certain that Tether was acting in a fraudulent manner, why not collect the $1 million bounty. I have no affinity for Tether LTD (or Hindenburg) but I suspect it is because Stofli, and others, do not have actual evidence. Perhaps Tether LTD is still operating in a fraudulent manner, but using innuendo or hearsay is not a valid argument.

On p. 98 he writes:

“This book is going to be called Jay Is Wrong and Zeke Is Right: The Cryptocurrency Story,” I said. “As a writer, you don’t want to be compromising in any way, you know? You don’t want to have ulterior motives.”

This is basically the opposite approach to Ben McKenzie, who in Easy Money writes about his $250,000 bet shorting the coin market… but doesn’t publicly disclose the bet until after the book is published. Conflict of interest?

Chapter 9: Crypto Pirates

This was a really solid chapter on SBF and FTX. In fact, I only had one quibble with it.

On p. 117 he writes:

Owning an exchange (FTX) and a firm that trades on it (Alameda) was an obvious conflict of interest. On Wall Street it wouldn’t have been allowed, due to the risk that the trading firm would be given preferential treatment or access to confidential information.

While I agree with the author, that this should not be allowed, it technically is not true in the U.S.

As mentioned in the review of Easy Money, an uneasy arrangement has been allowed at various eras in traditional markets: Glass-Steagall separated commercial banking from investment banking and was enacted in 1933. Fast forward sixty six years later, in 1999, most of it was repealed. Some economists such as Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman opined that this set the stage for the 2007-2008 financial crisis. Even after the financial crisis and a myriad of debates, Glass-Steagall was still not restored. Even today, too big to fail banks still have these conflicts of interest.

So yes, some U.S. stock exchanges may not have that specific conflict of interest, but a number of other intermediaries do.

Chapter 10: Imagine a Robin Hood Thing

On p. 120 he writes:

There was one other thing that was incongruous with Bankman-Fried’s public image: the itty-bitty matter of U.S. law. If Bankman-Fried had stayed in Berkeley, many of the bets FTX offered would’ve been not quite legal. Or entirely, deeply illegal. Nearly all the coins it listed would have been deemed unregistered securities offerings, like MasterCoin. The exchange itself didn’t comply with SEC trading rules either.

That could be true, but it probably would have been a stronger statement if the author had quoted or cited a U.S.-trained securities lawyer on that matter.

On p. 122 he writes:

“You’ve built up a good reputation,” I said, needling him a bit. “You could probably run some crypto scam and make a few billion dollars right now. By your logic, wouldn’t that make sense?” “Charities don’t want that money,” he said. “Reputation is so important for everything you do. And as soon as you start to think about the second-order effects, it starts to look worse and worse.”

It has been interesting to read this book and write the review during the SBF criminal trial. The book itself was introduced as evidence when SBF took the stand. While the passage above didn’t make it into testimony, in retrospect it was a pretty big self-own.

On p. 126 he writes:

In fact, by then, Tether had grown to 79 billion coins. And it was becoming clear that Bankman-Fried was a big enough user of Tether that he wasn’t likely to tell me if something worse was going on. The short sellers and conspiracy theorists kept promising to reveal some big secret, but it hadn’t happened.

I have my own theory as to why some of the conspiracy theorists went off the deep end, turning their notoriety into a cottage industry for continual media engagement. But putting that cynical view to the side, reporters should ask these folks to provide the receipts. And move on to other sources if they do not.

On p. 127 he writes:

The funds were not in the possession of shadowy North Koreans or some other group of cyberterrorists. The stolen billions were traced to a couple in their early thirties who lived in downtown Manhattan, not far from my place in Brooklyn. Their names were Ilya Lichtenstein and Heather Morgan. Judging from social media, the two didn’t exactly appear to be criminal geniuses.

I recall the first time I saw those names in the press and I asked a couple (trader) acquaintances in NY if they had ever heard of them. No one had. The next chapter illustrates why this book is a solid entry into the True Crime genre.

Chapter 11: “Let’s Get Weird”

On p. 135 he writes:

In 2021, a total of $3.2 billion in cryptocurrency was stolen from exchanges and decentralized finance (or DeFi) apps, in which crypto traders make deals directly with one another. That’s a hundred times more than the total stolen in all bank robberies in an average year in the United States.

Bank robbers need to step up their game, those are rookie numbers.

On p. 135 he writes:

Back in 2015, Bitfinex had set up a new security system after it lost about $400,000 of cryptocurrencies in a hack. Other exchanges generally mixed users’ coins together and stored the private keys on computers that weren’t connected to the internet, a practice known as “cold storage.” Bitfinex’s new system kept each user’s balance in a separate address on the blockchain, allowing customers to see for themselves where their money was. It used software from the crypto-security company BitGo.

Some background: the day Bitfinex was hacked (a 2nd time), some anti-government commentators, such as Andreas Antonopoulos falsely claimed that it was the fault of the CFTC. Recall that a few months prior, the CFTC fined Bitfinex for violating the CEA.

There is only so much time of in the day to fact-check, so hats off to Faux for not stumbling down the well-worn “its the governments fault” excuse. Maybe it is sometimes, but not that day.

On p. 135 he writes:

Michael Shaulov, a former coder for the Israeli Intelligence Corps and co-founder of the crypto-security firm Fireblocks, told me hacks like these generally don’t require a high level of technical expertise. Often, he said, the hardest part is crafting an email that tricks an insider into opening a malicious attachment. “The social-engineering vector is key,” he said.

Over the years I’ve had a chance to speak with people involved at a couple of the companies mentioned in this chapter. And while I have heard a single person singled out, it was a little disappointing that the criminal case against Ilya Lichtenstein and Heather Morgan didn’t say who or what was compromised.29

On p. 138 he writes:

They returned after a few weeks and then a third time a few weeks after that. “You sure you’re in the right building?” the doorman asked. (At the time, police were investigating the death of a prostitute in the tower across the street—surveillance video had shown men rolling a 55-gallon drum that concealed her dead body out of the building.) The agents assured him they were.

Faux’s never ending attention to detail strikes again.

On p. 142 he writes:

The arrest was national news. It was the largest seizure of stolen funds ever. “Today, the Department of Justice has dealt a major blow to cybercriminals looking to exploit cryptocurrency,” Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco said at a press conference. The TikTok commentariat tore through Morgan’s music videos, and within hours Razzlekhan was already a social media legend, having air-humped her fanny pack into the ranks of famous grifters. “The Bitcoin crimes are nothing compared to calling this shit rap,” Trevor Noah said on The Daily Show.

The amount of podcasts, videos, and obscure magazines and newspapers that Faux must have digested is impressive. Pretty solid zingers elsewhere too.

On p. 143 he writes:

Years after the Bitfinex heist, a fifth of the missing Bitcoins were still unaccounted for. Roughly $70 million worth had been sent to Hydra Market, a Russian dark-web site. No one knew where the money went from there, but on Hydra, vendors called “treasure men” were known to exchange crypto for shrink-wrapped packets of rubles that they buried in secret locations. It was possible there were underground bundles somewhere in Russia, waiting for Morgan and Lichtenstein to dig them up.

Is it just a matter of time before people randomly start digging for bundles of burried rubles? Shouldn’t there be a prediction market for this type of degen activity?

On p. 144 he writes:

The Bitcoins had been worth about $70 million when they were stolen. Devasini and his crew stood to recoup billions of dollars. It gave me little confidence in their abilities to safeguard money that their Bitcoins ended up in the hands of a pair of idiots, but having the coins sitting locked up in the couple’s wallets was probably a lucky break.

Based on the numbers mentioned in this book, there is a possibility that those high up Tether LTD are quite well off at this stage. Although clearly not at the same strata as Colin Platt.

On p. 144 he writes:

I quickly found that Mashinsky had an interesting history. I’d found a 1999 article in a defunct tech publication in which he listed a few very different businesses that he’d tried out after moving to the United States: “importing urea from Russia, selling Indonesian gold to Switzerland, and brokering poisonous sodium cyanide excavated in China for use by gold miners in the U.S.” He also said in the article that he wanted to get into the business of whole-body transplants. “Give an old person a new body—keep the head, keep the spine, and re-create the rest,” he said.

In another universe Mashinsky has taken Brains-in-a-vat mainstream. There you get a free whole-body transplant on the condition that an hour a day you solve captchas. Years later he is sued and charged with digital tomfoolery, for stealthily making it 20 hours a day; he accidentally created the plot of The Cookie Monster.

Chapter 12: “Click, Click, Click, Make Money, Make Money”

On p. 149 he writes:

Stone took his money out of stocks and went all-in on Ethereum, eventually starting Battlestar, which was supposed to help investors earn a return on their crypto holdings through what it called “institutional grade Staking-as-a-Service.” (Don’t ask.)

While I like some technical nitty gritty, rather than bore readers (or botch it like other authors have), Faux punts on describing what “institutional grade Staking-as-a-service” is. And that’s okay. With that said, he does mention “yield farming” a couple of sentences later but doesn’t really define it in the book.30

On p. 150 he writes:

By then, the ICO boom was over. It was no longer plausible for someone to announce they were going to create Dentacoin, a cryptocurrency for dentists, and raise millions of dollars —a real thing that happened in 2017. DeFi was different. It was based on “smart contracts.” These are, basically, simple programs that run on the blockchain. Remember that the Bitcoin blockchain is a two-column spreadsheet, and MasterCoin, Ethereum, and the like allowed for adding new columns that represented new coins. Now imagine if the spreadsheet added functions. Instead of just allowing users to add Bitcoins to one person’s row and subtract them from someone else’s, these smart contracts enabled them to swap one kind of coin for another, or make a loan to another user.

I think this could be a little unclear for readers and a paragraph break should be made with “DeFi was different.” Also, while users can create and deploy new assets via Mastercoin (renamed Omni), it doesn’t have a virtual machine like other “modern” chains do so its functionality is very limited compared with Ethereum.31

On p. 151 he writes:

DeFi used these smart contracts to create decentralized, anonymous versions of exchanges like Sam Bankman-Fried’s FTX.

Probably more accurate to say pseudonymous.

On p. 151 he writes:

“DeFi may not exist in January,” Mashinsky wrote. “What we want is for every DeFi player to have a Celsius account, so when the Ponzi runs exhaust themselves they will all park their coins with Celsius.”

Wow, just wow.

On p. 154 he writes:

His description of life in Puerto Rico sounded like a montage from a crypto version of The Wolf of Wall Street: “dancing, partying, drugs, beach.” Stone set up two big screens at the dining room table. He rarely looked up from them, even when his host threw weekly parties. As people danced around the room, he’d stare at the screens and snort lines of ketamine. Other crypto traders would bring their laptops too. Some preferred Adderall or cocaine. Stone liked to say he was one of the largest players in DeFi, a friend who hung out with him then told me, often yelling about hacks or how much money he was making. “He’d type loud, like he wanted people to know,” the friend said.

On p. 155 he writes:

Because it was crypto, all that money was stored on Stone’s laptop. It was as if Stone kept a billion dollars in bundles of hundreds, just sitting on his friend’s dining room table. The account was protected by a password, but Stone grew paranoid. He couldn’t sleep for more than a few hours at a time. He’d stay up until three in the morning trading, then start again at six or seven.

I’m not a master of memes but pretty certain an appropriate one for the passage above is: are ya winning, son?

On p. 155 he writes:

Mashinsky was claiming Celsius was safer than banks, but the company didn’t even have a system for tracking what Stone and its other traders were doing with the money. As one Celsius executive wrote in an internal email in December 2020: “As things stand currently, Celsius does not have a clear, real-time, and actionable view of our assets and liabilities.”

SMH.

On p. 157 he writes:

Mashinsky argued that crypto was better than dollars, because inflation would inevitably erode the value of all government-issued currency. I told Mashinsky I didn’t have any savings in cash, so it wasn’t like I was sitting on a pile of money that was getting less valuable. And I wasn’t worried about the safety of my bank account.

That old chestnut. J.P. Koning wrote a pretty good debunking of a similar narrative.

Chapter 13: Play to Earn

On p. 162 he writes:

Lapina started using his earnings to buy more teams of blobs, and he hired other people in town to play with them on their own phones. He let them keep 60 percent of whatever they won in the game. Before long, Lapina had more than a hundred people battling for him, including teachers, his grandmother, and even a police officer, who Lapina had to talk out of quitting the force.

Wow, had no idea how “viral” Axie was at that time.

On p. 162 he writes:

“It’s actually the beginning of the metaverse, in our opinion, just hiding in a very cute little game,” Aleksander Larsen, the Norwegian co-founder of Sky Mavis, said on a podcast. “I actually believe that Axie has the potential to impact the globe very heavily with letting people interact with the global economy, actually exiting their prisons, where they are born.”

Filtering through podcasts for this gem. Sounds like something VCs Congratulating Themselves would find.

On p. 163 he writes:

The returns didn’t strike the Filipinos I talked to as unreasonable. But a more sophisticated investor would have realized the daily rate of return was 8 percent—way, way too good to be true. At that rate, with earnings continually reinvested for ten months, Lapina and everyone else who bought a single set of Axies would be trillionaires.

Finally, a scheme on par with PTK.

On p. 163 he writes:

The only thing that kept the Axie economy afloat was new players buying in.

Because I’m overly pedantic I would probably have written, “the only thing that kept the Axie economy afloat at this price level” because technically Axie (the game) is still alive today.

On p. 166 he writes:

Quigan told me she and her husband were considering going abroad to Dubai to seek better-paying jobs. But she still checks the price of potions daily. “I don’t get angry,” she said. “I’m still optimistic that sometime, somehow, it will still go up.”

Probably could print that quote on a shirt and sell it a coin conference.

On p. 166 he writes:

QUIGAN MIGHT NOT have been angry, but I was. Crypto bros and Silicon Valley venture capitalists gave Filipinos false hope by promoting an unsustainable bubble based on a Pokémon knockoff as the future of work. And making matters worse, in March 2022, North Korean hackers broke into a sort-of crypto exchange affiliated with the game and made off with $600 million worth of stablecoins and Ether. The heist helped Kim Jong Un pay for test launches of ballistic missiles, according to U.S. officials. Instead of providing a new way for poor people to earn cash, Axie Infinity funneled their savings to a dictator’s weapons program.

Not a good look Bob.

Chapter 14: Ponzinomics

On p. 170 he quotes Anthony Scaramucci:

“These people are unbelievable the way they dress,” he said. “I’m here in a Brioni, these guys are in Lululemon pants. These guys are moving into the future. These are some of the worst-dressed people I ever met in my life.”

Yea, it’s not the fly-by-night scams to be concerned about, it is the clothing choices.

On p. 171 he writes:

As Lewis went on, Bankman-Fried tapped the toes of his silver New Balance sneakers, sometimes pressing his legs with his elbows as if to hold them still. It seemed like Lewis saw him as another one of the truth-telling, system-disrupting outsiders he liked to write about. But the author’s questions were so fawning, they seemed inappropriate for a journalist. Listening from the packed auditorium, I started to question whether Lewis was really writing a book, or if FTX had paid him to appear. (Lewis later told me that he had in fact come to report for his book and that he was not compensated.)

Was Lewis provided flights on the FTX jet? Either way, Michael Lewis was unhappy with Faux’s reporting on this topic, telling The New York Times in its review of Going Infinite:

I’ve never met Faux but I do not think he is on trial for defrauding customers for ~$8 billion in losses. Who knows, maybe Faux has been moonlighting as a North Korean hacker. How else could he track down VIPs at art shows?

On p. 172 he writes:

At a party for a project called Degenerate Trash Pandas, I asked one coder if crypto would ever be helpful for regular people. “Why is it that you think that is important?” he said to me, in a tone of total sincerity. “I really would like to know.”

Socially useful dapps? Get out of here.

On p. 173 he write:

Another crypto executive showed me a digital image of a sneaker that he bought for eight dollars, which he said had grown to be worth more than $1 million. He told me that recently, all owners of these imaginary sneakers had been issued an image of a box, which was itself worth $30,000. When he opened the box, he found another picture of sneakers and another box, each of them valuable in their own right. “It’s this never-ending Ponzi scheme,” he said, happily. “That’s what I call Ponzinomics.”

Reminds me of that SNL sketch with Tim Meadows and Will Ferrell with a Bible and a bar of gold:

On p. 175 he writes:

It struck me that almost any of the companies I’d heard about would be good fodder for an investigative story. But the thought of methodically gathering facts to disprove their ridiculous promises was exhausting. It reminded me of a maxim called the “bullshit asymmetry principle,” coined by an Italian programmer. He was describing the challenge of debunking falsehoods in the internet age. “The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it,” the programmer, Alberto Brandolini, wrote in 2013.

Another solid Tweet reference. Unfortunately Community Notes was not around in 2014-2016 which I think could have headed off some of the nonsense narratives.32

On p. 180 he writes:

Van der Velde seemed annoyed. He hinted that there was something in Tether’s past that he couldn’t reveal. “It’s very easy to invite a journalist into your office when you don’t have any battle damage,” he said. “Tether saved the whole industry. We had to carry those heavy loads. Sam had the luxury of making a nice clean start. Sam never had to deal with that.”